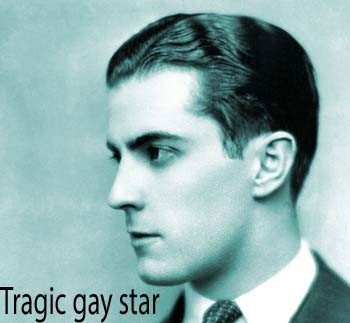

Tom Laughlin in Billy Jack.

Tom Laughlin: Billy Jack actor-filmmaker who died last week helped to revolutionize film distribution patterns in North America

Tom Laughlin, best known for the Billy Jack movies he wrote, directed, and starred in opposite his wife Delores Taylor (since 1954), died on Dec. 12 at Los Robles Hospital and Medical Center in Thousand Oaks, northwest of Los Angeles County. Tom Laughlin (born on Aug. 10, 1931, in Minneapolis) was 82; in the last dozen years or so, he suffered from a number of ailments, including cancer and a series of strokes.

Tom Laughlin movies: ‘The Delinquent’s and fighting with Robert Altman

In the mid-’50s, after acting in college plays and in his own stock company while attending university in Wisconsin, Tom Laughlin began landing small roles on television, e.g., Climax!, Navy Log, The Millionaire. At that time, he was also cast in minor parts in a handful of Hollywood movies, among them Vincente Minnelli’s drama Tea and Sympathy (1956), starring Deborah Kerr and John Kerr.

Tom Laughlin’s sole lead during that period was his portrayal of a disillusioned youth who joins a street gang in Robert Altman’s first feature, The Delinquents (1957), an independently made, micro-budget production shot in and around Kansas City.

According to Patrick McGilligan’s Robert Altman: Jumping Off the Cliff, The Delinquents was a difficult shoot, for “the square, free-wheeling Altman and the bohemian, mercurial Laughlin” did not get along. Tom Laughlin, in fact, wanted to quit the film, but was persuaded to stay on following a peace treaty with the future MASH, Nashville, and Gosford Park director.

Years later, as found on Jeff Stafford’s piece on The Delinquents, Robert Altman would describe Tom Laughlin as “’an unbelievable pain in the ass,’ totally egomaniacal, guilty that he had not become a priest, with a ‘big Catholic hang-up’ and a James Dean complex.”

Following The Delinquents, Laughlin would be seen in only a handful of minor roles in Hollywood films – e.g., Paul Wendko’s Gidget (1959), with Sandra Dee, Cliff Robertson, and James Darren; Joshua Logan’s South Pacific (1958), with John Kerr, Rossano Brazzi, and Mitzi Gaynor – in addition to a couple of little-seen personal, micro-budgeted independent projects.

His film career basically stalled, in 1959 Tom Laughlin and Delores Taylor joined forces to found a Montessori preschool in Santa Monica. Despite its initial success – the Montessori educational philosophy emphasizes human development techniques – the school went bankrupt in 1965.

That same year, Like Father, Like Son a.k.a. The Young Sinners, a morality tale Laughlin had directed, written, and produced in Milwaukee in 1960, came and went without causing much of a stir. Initially intended to be part of a trilogy entitled We Are All Christ, the film features Tom Laughlin as a college football star who reminisces about his troubled life while confessing his sins to a priest. Stefanie Powers costarred.

Tom Laughlin and the ‘Billy Jack’ movies: ‘Born Losers’

Two years later, Tom Laughlin – as actor, director (billed as T.C. Frank), and producer – was back on the big screen with the first Billy Jack movie, Born Losers / The Born Losers, a low-budget exploitation flick that became a surprising box office hit. In the film, Laughlin plays the part-white, part-Native American Vietnam War veteran Billy Jack, a martial-arts expert who comes to the rescue of a rape victim (played by Elizabeth James, who also doubled as the film’s screenwriter) and a whole town under siege by a brutal motorcycle gang.

Released by the second-rank American International Pictures, for two weekends in a row the $400,000-budgeted film featuring mostly unknowns displaced from the top of the North American box office chart Arthur Penn’s Warner Bros.-distributed Bonnie and Clyde, starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway.

According to the website The Numbers, Born Losers ultimately pulled in $36 million. (Note: the site doesn’t provide a source for that figure, which would represent approx. $241 million in 2013 dollars; also unclear is whether that amount refers to the film’s domestic box office grosses or to the distributor’s rentals.)

‘Billy Jack’: Tom Laughlin vs. Richard Zanuck and Richard Nixon

At first, things didn’t look good for the Born Losers sequel, Billy Jack, directed and produced by Laughlin, who also cowrote the screenplay with Delores Taylor. Inspired by the way Native Americans were treated in Taylor’s hometown of Winner, South Dakota, Billy Jack’s original draft had been written in 1954. Production on the self-financed film began in 1969, but was interrupted after American International Pictures backed away from the project. Richard Zanuck’s 20th Century Fox stepped in for a while, but conflicts arose as a result of the film’s politically charged message.

As per The Amazing Story Behind the Legend of Billy Jack, Zanuck “wanted to cut out all the scenes Tom Laughlin felt gave Billy Jack its ambience and message.” Worst of all, Zanuck, described as a “principal player in Nixon’s reelection campaign in California,” wanted to cut the city council sequence featuring the following bit of dialogue:

“The streets in our country are in turmoil,” recites a local student (played by Tom Laughlin and Delores Taylor’s daughter T.C.). “The universities are filled with students rebelling and rioting. Communists are seeking to destroy our country. Russia is threatening us with her might, and our Republic is in danger – yes, danger from within and without. We need law and order. Without law and order, our nation cannot survive.”

“You wanna know who wrote it?” asks another student. “Adolf Hitler wrote it in 1932, and everyone from Nixon’s cabinet to your council is repeating it today.”

Following a stand-off pitting 20th Century Fox – which held the Billy Jack negative in its possession – and Tom Laughlin and Delores Taylor – who held the film’s sound in their possession, Fox sold Billy Jack back to Laughlin for $100,000. It was then that Warner Bros. became involved in the film’s release.

Billy Jack with Tom Laughlin.

‘Billy Jack’: Tom Laughlin helped to revolutionize Hollywood’s film distribution system

Featuring the titular hero as a semi-mystical figure who, with a mixture of steely determination and purposeful violence, helps to rescue wild horses from becoming dog meat and allows an independent school to continue operating at an Indian reservation in Arizona – against the wishes of white reactionary bigots and ruthless capitalists – Billy Jack was a box office disappointment when released by Warner Bros. at, in Tom Laughlin’s words, “porno houses” (and drive-ins) in 1971. (Image: Tom Laughlin in Billy Jack.)

Unhappy with the studio’s handling of his film, Laughlin sued Warners. In May 1973, following a settlement with the studio, he began self-distributing Billy Jack at small-town movie theaters throughout the United States. He hired marketing expert, former United Artists honcho, and former film producer Max E. Youngstein (Fail-Safe, The Money Trap), who made use a film distribution system known as “four walling”: the distributor would rent a certain number of movie theaters in any given area for a week or two, keeping all or nearly all of the box office earnings; the exhibitors, for their part, kept the money collected from concession stand sales.

A key element of this particular distribution strategy was the use of saturated television – instead of print – ads specifically targeting various segments of the population. After all, the movie had to sell as many tickets as possible in only one or two weeks.

In the case of Billy Jack, results proved to be more than encouraging – they were phenomenal. As per the AFI’s notes on the film, Tom Laughlin’s $800,000-budgeted drama brought in more than $10 million (about $45 million today) over the course of twenty months. At the end of its run, the film’s box office rentals* reached $32.5 million (approximately $145 million today).

Hollywood adopts (and adapts) ‘Billy Jack’ film distribution system

As explained in David H. Cook’s Lost Illusions, later in 1973 Universal and Warner Bros. used similar tactics – targeted saturated TV ads, “four-walling” in specific markets – to distribute, respectively, Michael Crichton’s Westworld, starring Yul Brynner, and William Friedkin’s The Exorcist, starring Ellen Burstyn and Linda Blair. The latter film went on to become one of the biggest box office hits in history.

Tom Laughlin himself used similar methods for the release of the widely panned – but financially successful – The Trial of Billy Jack in 1974. One key difference was the film’s opening nationwide at more than 1,000 venues, a distribution strategy all but unheard of back then. The third Billy Jack movie eventually pulled in a reported $55 million (approx. $237 million today).

In the mid-’70s, the National Association of Theater Owners sued against the practice of four-walling, which was temporarily stalled. Even so, saturated – and increasingly wider – releases, an emphasis on opening weekend box office grosses, and the use of targeted TV ads became the usual film distribution system for the Hollywood studio’s major offerings, from Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (coincidentally coproduced by Richard Zanuck) all the way to Shane Black’s Iron Man 3, Francis Lawrence’s The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, and Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug.

‘Billy Jack’: Progressive or reactionary?

Though on the surface a progressive, liberal-minded effort to counterbalance the likes of Clint Eastwood in Dirty Harry and Charles Bronson in Death Wish, Tom Laughlin’s Billy Jack irked some who felt the film supported vigilantism and violence in the name of peace.

“Fans likened Tom and his alter ego, Billy, to the prophet Jeremiah, to Don Juan (not the Casanova but the Castañeda shaman) and to Ralph Nader,” Barbara Wilkins would write for People magazine in 1975. “And any exploitative violence behind that blockbuster box office, Laughlin declared, was the figment of eastern critical effetism.” (Curiously, Wilkins adds that “similarly discounted were the stories of Laughlin, with his torrential temper, hurling a clock-radio at his secretary or stirring so much terror on the set that even extras got sick to their stomachs.”)

Whether or not a “figment of eastern critical effetism,” upon its release the Washing Post called Billy Jack, “a horrendously self-righteous and devious action movie,” while Roger Ebert complained: “Billy Jack seems to be saying the same thing as Born Losers, that a gun is better than a constitution in the enforcement of justice. Is democracy totally obsolete, then? Is our only hope that the good fascists defeat the bad fascists? Laughlin and Taylor are still asking themselves these questions, and Billy Jack arrives at a conclusion that is only slightly more encouraging.”

Itself derivative of countless Hollywood Westerns and crime dramas – e.g., William S. Hart Westerns of the 1910s, Alan Ladd in Shane – Billy Jack, along with The Born Losers, also turned out to be quite influential. Whether directly or indirectly, these two Tom Laughlin efforts can be seen as precursors to movies such as Ted Kotcheff’s First Blood (1982), starring Sylvester Stallone; and, to some extent, Phil Karlson’s immensely successful Walking Tall (1974), starring Joe Don Baker, and even Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976), with Robert De Niro as the titular vigilante. And on television, there was Kung Fu (Oct. 1972- Apr. 1975), with David Carradine as another righteous, semi-mystical, ethnically mixed martial-arts expert who is invariably forced to commit violence In the Name of the Common Good.

* Rentals refer to the percentage of the box office gross that goes to the distributors. Due to its different release patterns in 1971 and 1973, Billy Jack’s final box office gross is impossible to calculate without more detailed information on how the film’s rentals were generated. Nowadays, box office grosses (not rentals) are used to measure a film’s success.

Billy Jack Goes to Washington poster with Tom Laughlin.

Tom Laughlin: ‘Billy Jack’ movie franchise comes to an end; U.S. government, Hollywood studios blamed

In 1975, Tom Laughlin’s self-produced Western The Master Gunfighter – a remake of Hideo Gosha’s samurai actioner Goyokin, costarring Ron O’Neal and Barbara Carrera – bombed at the box office after opening at more than 1,000 locations. According to People, Laughlin had spent $3.5 million to market the $3.5 million production, having hired John Rubel, assistant secretary of defense under Robert McNamara, to plan the film’s distribution tactics.

Financially depleted and embroiled in more lawsuits against Warner Bros., Laughlin embarked on the Billy Jack serie’s fourth – and, as it turned out – final film, Billy Jack Goes to Washington. A 1977 Frank Capra Jr.-produced reboot of Frank Capra’s 1939 classic Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Laughlin’s final directing effort was barely seen even in its drastically edited form. (I haven’t been able to find international figures for the Billy Jack movies, but they seem to have been a strictly American box office phenomenon.)

At the time, Tom Laughlin accused Warners and its president, Frank Wells, of pressuring banks to withdraw their support for Billy Jack Goes to Washington. Nearly three decades later, he would also blame the U.S. government for his film’s failure, telling CNN’s Showbiz Tonight in 2005:

At a private screening, [Democratic Indiana] Senator Vance Hartke got up, because [Billy Jack Goes to Washington] was about how the Senate was bought out by the nuclear industry. He got up and charged me. Walter Cronkite’s daughter was there, [and] Lucille Ball. And he said, ‘You’ll never get this released. This house you have, everything will be destroyed.’

In Billy Jack Goes to Washington, Tom Laughlin plays the old James Stewart role, an idealist who discovers he has become a pawn for a group of unscrupulous politicians with a dangerous agenda. Delores Taylor is the Jean Arthur-like leading lady, while E.G. Marshall (in the old Claude Rains role) and Sam Wanamaker are two key supporting players in a cast that also included Lucille Ball’s daughter Lucie Arnaz, Suzanne Sommers, Peter Donat, and veterans Kent Smith and Pat O’Brien.

The Return of Billy Jack, in which the returning character was to go after child pornographers, was scrapped in 1985 after Laughlin suffered an injury. About two decades later, there were plans for another Billy Jack movie that never got off the ground: Billy Jack’s Crusade to End the War in Iraq and Restore America to Its Moral Purpose a.k.a. Billy Jack’s Moral Revolution.

Tom Laughlin for president of the United States

Besides his film work, Tom Laughlin was also known for his several failed runs for the presidency of the United States. In 1991, he told the Milwaukee Sentinel, “I am the least qualified person I know to be President, except George Bush. I hate politics; it’s just a pit of deceit. It’s a game and a lie and a double deal.”

At that time, Laughlin protested at being excluded from the primary ballot in Wisconsin. Also unhappy was the Milwaukee Sentinel, which lambasted the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s decision to block Tom Laughlin while allowing the inclusion of former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke, “imprisoned Democrat extremist” Lyndon H. La Rouche Jr., and a “Dodgeville chicken farmer.” Later on, Laughlin became an “advisor” to independent U.S. presidential candidate Ross Perot.

In politics, Laughlin also took to task far-right Christians and their “Christo-fascist movement.” On his website, billyjack.com, he referred to them as “false Evangelicals” and “false prophets.”

Among his numerous other off-screen activities, Tom Laughlin wrote several books on psychology including The Psychology of Cancer and Jungian Psychology vol. 2: Jungian Theory and Therapy, and became involved in the issue of domestic violence after witnessing a neighbor – a police officer – beating his wife.

Note: Actor and filmmaker Tom Laughlin is not to be confused with the wrestler Thomas James “Tom” Laughlin, best known as Tommy Dreamer.

Tom Laughlin article sources

Billy Jack’s city council session information via a cached page from billyjack.com. Tom Laughlin Billy Jack photo: National Student Film Corporation / Warner Bros.

Besides the news outlets and publications mentioned in the body of this three-part Tom Laughlin article, here are the other key sources used for this piece: The New American Cinema, edited by Jon Lewis; Lucien Rhode’s “The Return of Billy Jack,” at inc.com; David A. Cook’s Lost Illusions: American Cinema in the Shadow of Watergate and Vietnam, 1970; D.K. Holm’s Independent Cinema; Justin Wyatt’s High Concept: Movies and Marketing in Hollywood; Seeing Red – Hollywood’s Pixeled Skins: American Indians and Film, edited by LeAnne Howe, Harvey Markowitz, and Denise K. Cummings; Jack Mathew’s “Tom Laughlin Throws Black Hat into the Ring” in the Los Angeles Times; and Phil Dyess-Nugent’s Tom Laughlin obit for A.V. Club.

“We despise both political parties, really loathe them. … We the people have no representative of any kind. It’s now the multinationals. They’ve taken over. It’s no different than the ’70s, but it’s gotten worse. And if you use words like ‘impeachment’ or ‘fascist’ you’re a nut on a soapbox.” Tom Laughlin, as quoted in The New York Times. Laughlin, along with his wife and Billy Jack costar Delores Taylor had plans for a new movie that would tackle drug abuse, Christian zealotry in American politics, and the war in Iraq.

Tom Laughlin Billy Jack photo: National Student Film Corporation | Warner Bros.