Cowrie Shells and their Imitations as Ornamental Amulets in Egypt and the Near East

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Abstract

AI

AI

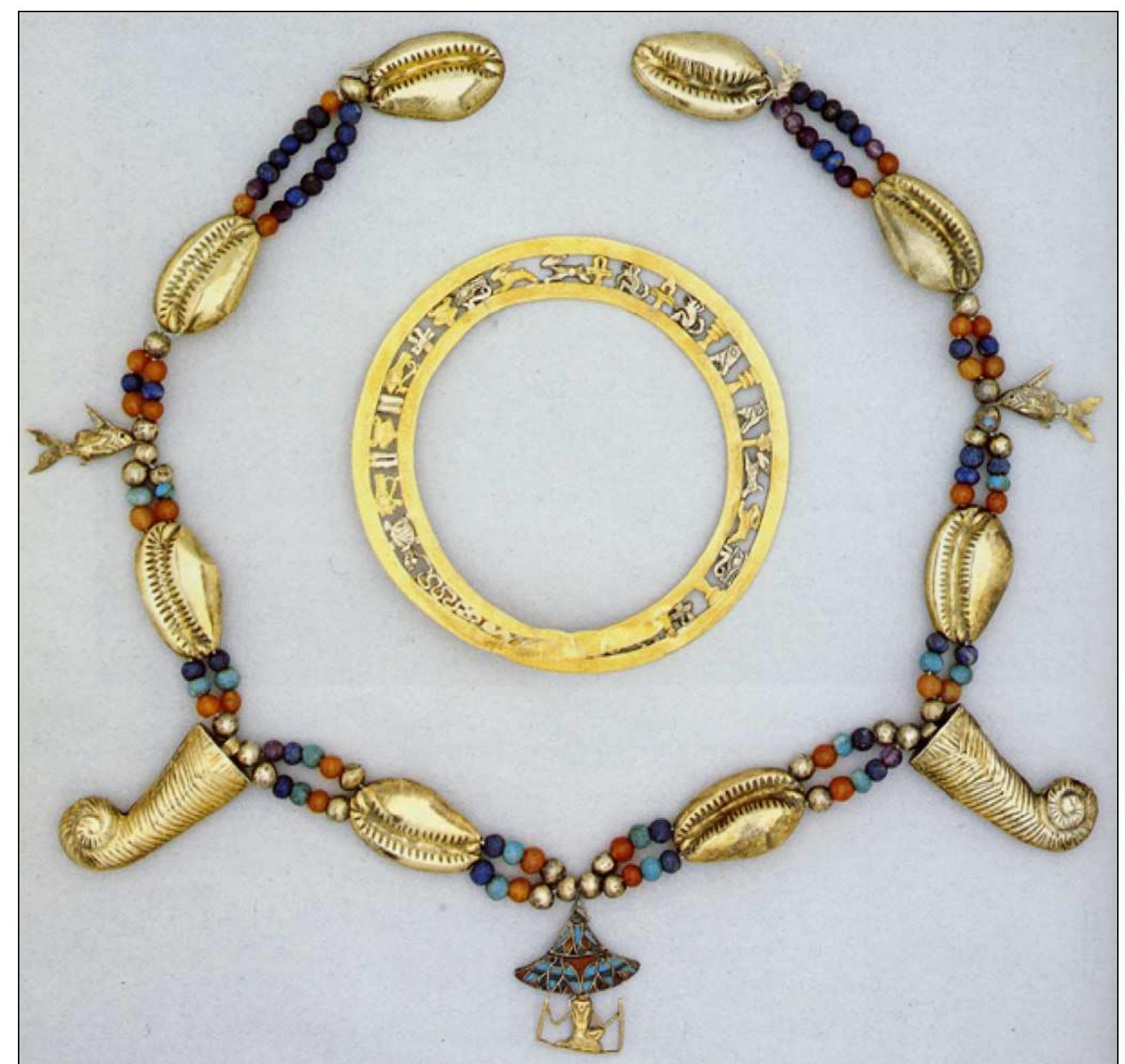

Cowrie shells, particularly from the genus Cypraea, have been found widely throughout archaeological sites in the Near East, signifying their importance as ornamental and amuletic objects from ancient times. While these shells were sometimes used as currency, their primary value lay in their role as protective amulets, symbolizing fertility and protection against malevolent forces. The tradition of creativity extended to the imitation of cowrie shells in various materials, enhancing their symbolic significance. This research sheds light on the diverse archaeological contexts in which cowries and their imitations appear, reflecting their socio-cultural significance across different ancient societies.

Key takeaways

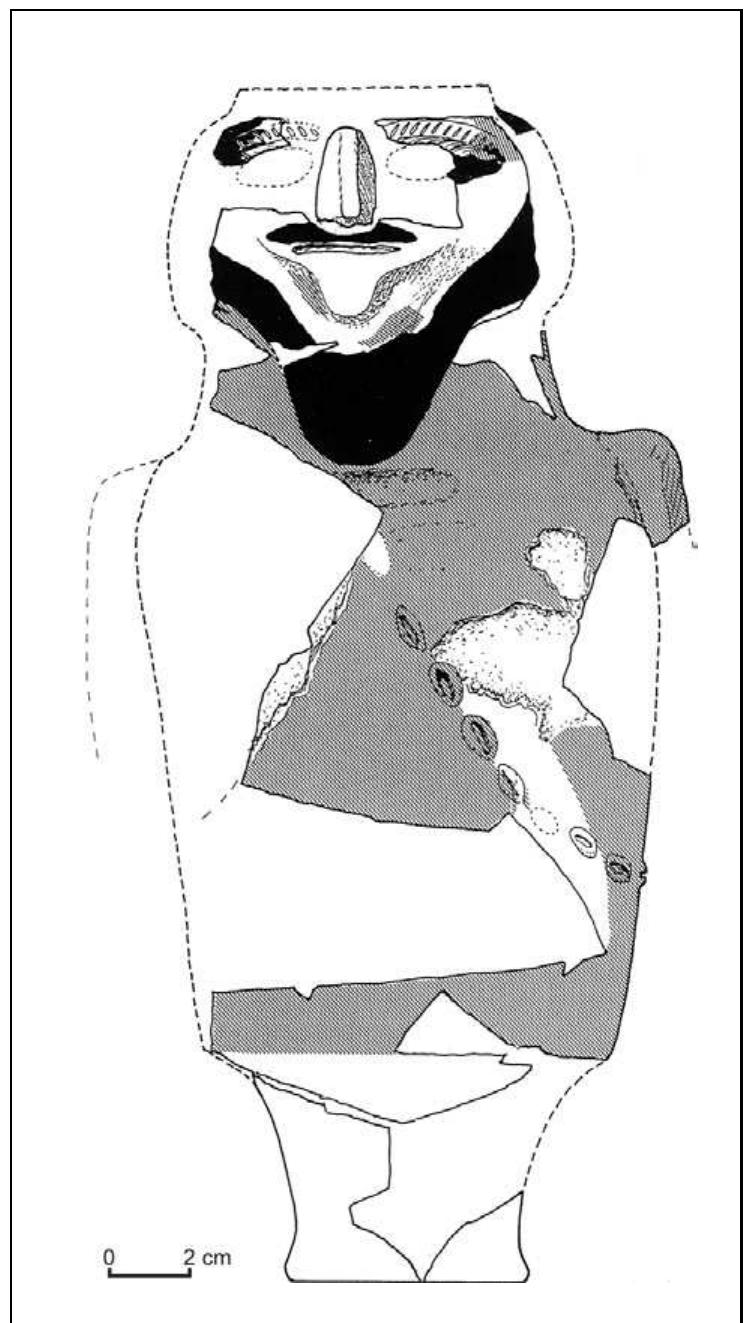

- coWrie shells a recurrent type of shell found in different archaeological contexts is the cowrie (or cowry, plural cowries), a common name for a group of small to large marine gastropods of the Cypraeidae family.

- The importance of cowries extends throughout the fertile crescent as noted in neo-assyrian records that specifically mention cowrie shells alongside precious items, as well as silver and gold (e.g., fales, postgate [eds] 1992: 66, 68, 72, 118, 129).

- as a result, cowries were connected with fertility, pregnancy and hence the recurrent association of cowrie shells with women and young girls.

- imitations of coWries in other materials further evidence of the high regard in which cowries were held, comes from imitations of the cowrie form in precious metals, stone and siliceous materials, such as faience and glass.

- as the form of the shell and not the shell itself was of significance, the use of other materials of symbolic power to produce the cowrie form served to emulate and enhance the cowrie's amuletic protective powers.

Related papers

Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy, 2019

Recent excavations at the sites of Dibba, Saruq al-Hadid and Sumhuram/Khor Rori have, together, produced a very substantial assemblage of worked shell discs dating to two broad but non-contiguous periods-the early first millennium BCE and the late centuries BCE and early centuries CE. In this article, we present and review the corpus of worked shell discs from these southern Arabian sites and contextualise them through comparison with worked shell discs from controlled excavations in Arabia and neighbouring regions of the ancient Near East, as well as unprovenanced antiquities in international museum collections. This research highlights the long-distance cultural connections and significance of this category of shell artefacts, aspects of their production, exchange and circulation, and their multi-valent ancient uses and modern interpretations. The three key sites present diverse aspects of the archaeological record of late prehistoric and early historic Arabia (Fig. 1). Dibba, located in the Omani area of the port of Dibba on the Gulf of Oman, is a burial complex comprising two large subterranean collective tombs designated LCG-1 and LCG-2 that were in use from the end of the Late Bronze Age to the early Iron Age (ca. 1500-700 BCE). Excavations there by the Ministry of Heritage and Culture of the Sultanate of Oman have recovered the primary and secondary burials of hundreds of individuals of both sexes and different age groups, together with thousands of grave offerings from the tombs and pits dug nearby, including cuts of animal meat, ceramics and softstone vessels, beads of semi-precious stones, and particularly

2019

A number of Middle Stone Age (MSA) assemblages in northern Africa, as well as a few in South Africa and the eastern Mediterranean, preserve small mollusk shells, most notably estuarine and marine members of the subfamily Nassariinae (e.g., Nassarius kraussianus, N. circumcinctus, and Tritia gibbosula). In most of these instances, these small shells have additional holes, which were made by natural processes or humans. These holes have led some researchers to interpret these shells as having been used as beads or ornaments. Studies of traces from wear and ocher residues on these shells have supported this interpretation, but most lack traces of manufacturing. The antiquity of such shells in the archaeological record extends back to the early Late Pleistocene, and as such, these shells may provide the earliest consistent and geographically widespread evidence for human personal ornamentation in the world. Here we review what is known about each of these assemblages and their contexts—...

Études et Travaux, 2021

At the archaeological site of Marina el-Alamein in Egypt, many monuments and everyday objects feature motifs related to Aphrodite and her cult. One recurring theme is the seashell that lamps are often decorated with. In one case, it accompanies the depiction of the goddess herself. This article collects oil lamps with the image of a scallop shell from the research of the Polish-Egyptian Conservation Mission, as well as already published specimens from earlier archaeological research. It has been noted to date that this motif is one of the most common on lamps found in Marina el-Alamein. Shells also appear on architectural elements – in the finials of niches with a religious purpose, located in the main reception halls of houses. In such aediculae they are well exposed, but the use of shells does not arise from the shape of the architectural framing. Therefore, other reasons, possibly symbolic ones, for including this motif in decoration should be considered. Full-text PDF available here: http://www.etudesettravaux.iksiopan.pl/images/etudtrav/EtudTrav_otwarte/EtudTrav_34/EtudTrav_34_04_Bakowska-Czerner_Czerner_medium.pdf

In Teotihuacan ancient city, at the beginning and during Temple of Feathered Serpent construction (150-200 ad), some ceremonies take place in which were offered several persons. Some of them wore vestments composed by many small seashell objects. This research's objective is to give to knowledge the seashell vestments wore by people offered and some technological procedures in seashell pieces manufacture. Through the analysis of manufacture traces on these objects with Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and also by experimental procedures was possible to determine processes and tools used in these ritual vestments production.

Related topics

Related papers

Southeastern Archaeology, 2018

In the papers assembled here, five scholars focus on shell beads at site, watershed, and regional scales. Themes include manufacturing techniques such as bore size discussions, changes in bead preferences over time and geography, the appearance of beaded regalia, and shell bead meaning. Claassen's paper addresses the beads at Late Archaic Indian Knoll; Connaway discusses

Molluscs in Archaeology, 2017

A guide to the field and laboratory techniques reccommended for collecting and processing marine shells from archaeological sites

2005

Shells are first purposefully collected in the Middle Palaeolithic, but their first systematic exploitation to serve as beads is in the Upper Palaeolithic. Small gastropods, especially Columbella rustica and Nassarius gibbosulus are usually chosen, some of them naturally abraded ready-to-use beads. This tradition continues throughout the Epi-Palaeolithic. The Natufian culture marks a change expressed in both larger quantities and diversity of species, and an increased preference for Dentalium. The economic changes from hunter-gatherers to farmers that characterize the Neolithic period are also expressed in new strategies of shell exploitation. Those include larger numbers of species that are collected, their use for making artifacts and not only simple shell beads, and their apparent use in exchange systems whose purpose is to provide food. In addition, more diverse methods are used for working the shells, resulting in such "prestige" items as Mother-of-Pearl pendants. Dozens of shell species are made into beads during this period, especially in the desert areas where Red Sea species are collected. The Mediterranean zone is distinguished by smaller assemblages dominated by Glycymeris and Cerastoderma.

Amir Golani

Amir Golani