Jumpman blocks photographer's shot at copyright claim

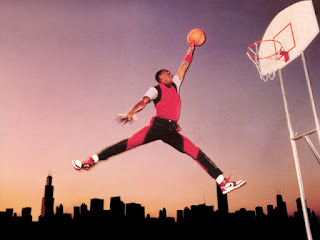

In January 2015 the CopyKat covered the case brought by photographer Jacobus Rentmeester against sporting apparel giant Nike, concerning Rentmeester's 1984 photograph of world-famous basketball star Michael “Air” Jordan, who was warming up for the Los Angeles summer Olympic games. Rentmeester had Jordan use a long horizontal jump technique known in ballet as a 'grand jete.’ It’s worth noting here that the jump itself is unusual for basketball and not something Jordan would have done in normal practice - so in effect a pose.

In January 2015 the CopyKat covered the case brought by photographer Jacobus Rentmeester against sporting apparel giant Nike, concerning Rentmeester's 1984 photograph of world-famous basketball star Michael “Air” Jordan, who was warming up for the Los Angeles summer Olympic games. Rentmeester had Jordan use a long horizontal jump technique known in ballet as a 'grand jete.’ It’s worth noting here that the jump itself is unusual for basketball and not something Jordan would have done in normal practice - so in effect a pose. Rentmeester allowed Nike to use the image for a temporary advertising campaign, but In 2014, Rentmeester accused Nike of copyright infringement. His lawsuit alleged that the sports giant copied his carefully choreographed picture using Jordan's left hand to slam dunk the ball. The “jumpman” silhouette logo is known the world over, and is used to promote Nike’s Air Jordan brand of basketball shoes and sportswear. According to Reuters, The Jordan brand now generates $3.1 billion of annual revenue for Oregon, USA headquartered Nike.

Rentmeester’s case was dismissed in June 2015 (this was covered by the CopyKat here), with the judge finding that the only similarity between Rentmeester’s photograph and Nike’s “Jumpman” logo was that of Jordan’s pose. The poses were not substantially similar and the District Court of Oregon dismissed Rentmeester’s claims. You can read a very good analysis of this decision over at the IPKat here.

Rentmeester subsequently appealed. However, in a In a 2-1 decision, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has upheld the original decision. In his judgement, Circuit Judge Paul Watford wrote that while both images “capture Michael Jordan in a leaping pose inspired by ballet’s grand jeté,” they were not substantially similar because of differences in setting, lighting and other elements. He added that “all the Nike photographer did [was] build freely upon the ideas and information conveyed by [Rentmeester’s earlier] work.”

The case is Rentmeester v Nike Inc, 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, No. 15-35509 and also see an updateon the IP Kat here)

Playboy has failed in its attempts to claim that a hyperlink to copyright-infringing content at Imgur and YouTube is itself illegal.

In November of last year, Playboy filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against Happy Mutants, the parent company of website Boing Boing. Boing Boing calls itself “a Directory of Mostly Wonderful Things,” and in 2016, provided a link to a separate gallery of "Every Playboy Playmate Centerfold Ever," hosted on imgur.

The subject matter of the suit included 477 photographs of models, known as "centerfolds." Playboy owns these centerfold images and argued that by linking to online versions of these photos, Boing Boing used, distributed, and exploited said images in websites without Playboy's authorisation or consent. Playboy further accused Boing Boing of vicarious

In a Court order, US District Judge Fernando Olguin noted the court was “skeptical that plaintiff has sufficiently alleged facts to support either its inducement or material contribution theories of copyright infringement.” Olguin allowed Playboy to amend their claims and resubmit, but Playboy failed to do so before the 26 February deadline.

In their press release, Boing Boing thanked their “brilliant attorneys” at the Electronic Frontier Foundation for “standing up to "Playboy's misguided and imaginy claims." EFF explained it was “hard to understand why Playboy brought this case in the first place, turning its legal firepower on a small news and commentary website that hadn’t uploaded or hosted any infringing content.”

Responding to a journalist’s story on the case, Playboy provided a statement which continued the assertion that Boing Boing "is supporting and contributing to privacy and content creators should not tolerate it.” And although they are not filing an amended complaint at this time, Playboy “will continue to vigorously enforce our intellectual property rights against infringement.” Image by Robobobobo and used under a Creative Commons Licence.

EU Recommendations formalise earlier guidelines on IPR enforcement

The European Commission has released a new statement, entitled “A Europe that protects: Commission reinforces EU response to illegal content online.”

The Recommendation gives formal effect to the political guidelines set out in the Communication on tackling illegal content online, first presented by the Commission in September 2017.

In that earlier Communication, the Commission promised to monitor progress in tackling illegal content, and assess whether additional measures are needed to ensure the swift and proactive detection and removal of such content. The Commission focuses on detection and removal of illegal content through both reactive (so called 'notice and action') and proactive measures.

These Recommendations are aimed at European Member States, as well as companies, and are to be used as initial proactive steps before the Commission determines whether new legislation should be proposed. The Stronger procedures suggested include better safeguards and full respect of fundamental rights, freedom of expression and data protection rules, as well as utilisation of more efficient tools and proactive technologies.

Interestingly, the Commission suggests that shared responsibility could particularly benefit smaller platforms with more limited resources and expertise in halting infringement. In particular, the Commission recommends that industry should, through voluntary arrangements, cooperate and share experiences, best practices and technological solutions, including tools allowing for automatic detection.

In terms of next steps, The Commission will continue analysing the progress made and will launch a public consultation later this spring.

You cannot copyright the dolphins!

The depiction of two dolphins crossing underwater is an "idea that is first found in nature," and therefore cannot be the subject of copyright protection, as per the U.S. Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit decision in the case of Folkens v Wyland.

Peter A. Folkens is wildlife artist who, nearly 40 years ago, drew an illustration of two dolphins crossing each other underwater. The pen and ink artwork depicts one dolphin swimming vertically and the other swimming horizontally.

Robert Wyland painted “Life in the Living Sea,” an underwater scene of two dolphins crossing underwater. Folkens' drawing, was adapted for use on an inexpensive Greenpeace charity postcard. On the other hand, Wyland sells art and merchandise through his Wyland Worldwide business, reported to make $100 million annually (LA Weekly).

Although the artworks are different in many respects - colour, lighting, and medium - there are certain similarities, with the primary similarity (similar to the Rentmeester v Nike case we mentioned above) being the "pose."

A trial judge first reviewed the works to determine if they were "substantially similar," and decided that this pose was a natural position incapable of protection under copyright law. Folkens appealed, but the Ninth Circuit has upheld the original decision.

In its judgement, the Ninth Circuit explained that despite this similar positioning of the dolphins, a pose is not ordinarily copyrightable unless combined with something else. In particular, “a collection of unprotectable elements - pose, attitude, gesture, muscle structure, facial expression, coat, and texture - may earn “thin copyright” protection that extends to situations where many parts of the work are present in another work.”

Folkens attempted to argue that the dolphins he drew are not exhibiting natural behaviour, because photos upon which he based his illustration on were of dolphins posed by professional animal trainers in an enclosed environment. However, Wyland’s counter-argument included an assertion that animal trainers can pose animals to capture positions that naturally occur in the wild.

This “idea” of crossing dolphins was first expressed in nature, and was therefore held by the court to be “within the common heritage of humankind.” Accordingly, no artist may use copyright law to prevent others from depicting this ecological idea. Is this a case of “scene a faire” gone too far? Does it demonstrate that any “natural” pose by anyone (or any animal) is incapable of copyright protection? For the benefit of further analysis, this CopyKat would have preferred the matter go to trial, rather than conclude by way of summary judgment.

Project Gutenberg: the German edition - laudable, but still infringing!

Project Gutenberg is an American website which offers 56,000 free books, many of which have had their copyright expired in the United States. Such classics available include Pride and Prejudice, Heart of Darkness, Frankenstein, A Tale of Two Cities, Moby Dick, and Jane Eyre. The website is run on servers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and is classified as a non-profit charity organisation under American law. The website is a volunteer effort which relies mostly on donations from the public, "to digitise and archive cultural works to encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks."

Despite the noble cause of making literature available at no or low cost to the masses, a recent ruling (https://cand.pglaf.org/germany/gutenberg-lawsuit-judgement-EN.pdf ) against Project Gutenberg has resulted in the website being geo-blocked for all visitors attempting to access the site from Germany. The claimants in the case are the copyright owners of 18 German language books, written by three authors, each of whom died in the 1950s. In Germany, the term of copyright protection for literary works is "life plus 70 years," which differs from the US approach for works published before 1978 where the works would be in the public domain. They are not in Germany.

Despite the noble cause of making literature available at no or low cost to the masses, a recent ruling (https://cand.pglaf.org/germany/gutenberg-lawsuit-judgement-EN.pdf ) against Project Gutenberg has resulted in the website being geo-blocked for all visitors attempting to access the site from Germany. The claimants in the case are the copyright owners of 18 German language books, written by three authors, each of whom died in the 1950s. In Germany, the term of copyright protection for literary works is "life plus 70 years," which differs from the US approach for works published before 1978 where the works would be in the public domain. They are not in Germany.

The copyright holders of these works notified Project Gutenberg of their alleged infringement back in 2015. In early February 2018, the District Court of Frankfurt am Main approved the claimant's "cease and desist" request to remove and block access to the 18 works in question. The claimants also requested administrative fines, damages, and information in respect of how many times each work was accessed from the website.

The Court reasoned that it was worth taking into account the fact that the works in dispute are in the public domain in the United States. This however "does not justify the public access provided in Germany, without regard for the fact that the works are still protected by copyright in Germany." The judgement also cited Project Gutenberg's own T&Cs in its decision, noting that the website considers its mission to be "making copies of literary works available to everyone, everywhere." While this broad statement may seem innocuous and idealistic, the court used this to support its findings that Project Gutenberg could not reasonably limit itself as an American-only website.

A key point in this matter is the question of jurisdiction. While Project Gutenberg is based in the USA, the claimants successfully argued that as the works were in German and parts of the website itself had been translated into German, the website was indeed "targeted at Germans." Furthermore, even if the website had not been intended for German audiences, that the infringement occured in Germany is sufficient grounds to bring the claim in German court.

While Project Gutenberg was only required to remove the 18 works listed in the lawsuit, the organisation has blocked its entire website in Germany to protect itself from any further potential lawsuits on similar grounds (see the Q&A here https://cand.pglaf.org/germany/index.html )

Project Gutenberg is planning to appeal the decision. There is more on the IPKat here at http://ipkitten.blogspot.co.uk/2018/03/gutenbergorg-loses-to-german-publisher.html

This CopyKat by Kelsey Farish