Gianluca Vacchi is a social media influencer and DJ, who has

more than 12 million followers on Instagram. He appeared last year in a commercial

(do not watch while drinking) for the Bank of Georgia, Europe, which was so

successful that “that many United States

residents registered as clients of the bank” (because nothing gives you

more confidence than a Santa Claus in an orange satin robe).

While Italian and living in Milan, Vacchi

travels around the world to dance on roof tops, DJing, and generally having a

good time. He chose Mr. Enjoy as his nickname. After all, as another Italian

influencer, who also meddled a bit with music, urged us: “Godiam, la tazza e il cantico, La notte abbella e il riso. »

But Vacchi is not enjoying two of online

investing company E*Trade’s commercials, [here

is the other one] which were produced in mid-2017, where a middle-aged

man, presented as “your boss,” is featured dancing with abandon (with who?)…

with scantily dressed women.

Vacchi has just filed

suit in the Southern District of New York against E*Trade, claiming “copyright infringement, as well as false

endorsement and misappropriation of protectable character, protectable scenes,

and image and persona of “the coolest man on Instagram.” Will he be

successful?

New York Civil Rights Law §§ 50 and 51 is

the state of New York’s only right to privacy, which is not otherwise

recognized by its common law. The statute makes it a misdemeanor to use the name,

portrait or picture of a living person for advertising or trade purposes

without prior written consent.

The E*Trade commercials are certainly “for advertising or trade purposes.” What

is less certain, however, is whether the “name, portrait, or picture” of Vacchi

has been used by Defendant.

Protecting

the Persona?

“In fact, even a simple Google search for

“dancing millionaire” inevitably shows Plaintiff in the top results”

(Complaint).

Plaintiff claims a use of his image and his

persona.

New York courts have recognized

that using a "lookalike" of a well-known personality for commercial

purposes is a violation of New York Civil Rights Law §§ 50 and 51. In this

case, a lookalike of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis has been featured in a Dior ad.

The court noted that “Plaintiff's name

appears nowhere in the advertisement. Nevertheless, the picture of a well-known

personality, used in an ad and instantly recognizable, will still serve as a

badge of approval for that commercial product.” In our case, Vacchi’s name

is not used in the commercial either.

Lindsay

Lohan was not able to convince the courts last

year either that Take-Two Interactive Software, the developer and distributor

of the Grand Theft Auto V video game, had used her likeness and persona to

create the character Lacey Jonas (see here

and here).

But the case was about a video game, not an advertisement, and the court in

Onassis v. Dior distinguished artistic from commercial endeavors.

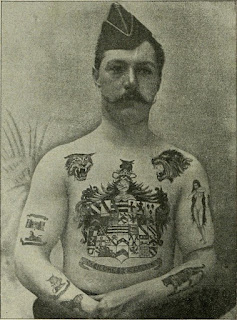

In our case, Plaintiff is a middle aged

man, with trimmed grey beard and hair, a toned and tattooed body, and a

propensity to take pictures of himself while bare chested. This is his image, his likeness, his

resemblance.

Plaintiff claims that Defendant used a “clone of Vacchi, dancing with women on a

boat while DJ’ing: conduct that based upon numerous YouTube videos,

photographs, and music videos created and published by Vacchi, has become

synonymous with the image and persona,” and describes “the E*Trade Character [as]

a heavily-tattooed male with bare torso

dancing with a beautiful female companion.”

Vacchi self-described persona is “the coolest man on Instagram,” and he

very well may be if cool is defined by sunsets seen from high rise balconies,

partying, the beaches, dancing around rooftop swimming pools, and leopard

cushions. No coupon clipping for him.

So Plaintiff’s persona could be: man +

middle-aged + toned and tattooed body + glasses + dancing + trim gray beard +

exotic locales + women in teeny weeny bathing suits. This could also describe

an aged James Bond after one too many stirred Martinis led him to the tattoo parlor,

or Queequeg if Moby-Dick had shed some blubber and got a bikini wax.

The E*Trade character is a middle-aged man, with glasses, bare chested, with tattoos,

dancing with young women in bathing suits, on a yacht. He wears suspenders, as

does Plaintiff sometimes.

It could be argued, as in the Onassis v.

Dior case, that “plaintiff's identity was

impermissibly misappropriated for the purposes of trade and advertising, and

that it makes no difference if the picture used to establish that identity was

genuine or counterfeit.” Plaintiff would still need to prove that Defendant

used his image. Or maybe it meant to portray the

Most Interesting Man in the World.

Copyright

Infringement

Plaintiff also claims that Defendant’s videos

are infringing derivative works and that

“E*Trade’s commercial is simply a rip-off

of a number of videos created and published by Vacchi over the years.”

Plaintiff regularly posts short videos on

his Instagram account, featuring him and other persons in exotic locales. He is

seen doing less than mundane activities, such as tattooing a female doll

(cringe alert on this one), or pedaling on a stationary bike in his private

jet.

Plaintiff did not obtain a registration for

these videos before filing suit, because “Plaintiff

is a foreign citizen and did not register all of his videos and photos in the

United States.“

This is too bad, as the U.S. Supreme Court held

last month, in Fourth Estate Public Benefit Corp. v. Wallstreet.com LLC, that a

plaintiff claiming copyright infringement must first register the work with the

U.S. copyright Office before filing suit.

Plaintiff’s Instagram videos are probably

not original enough to be protected by copyright anyway. The Copyright Office

appears to be less and less inclined these days [see here

and here]

to register such works, because they are

not original enough to be worthy of copyright protection.

The videos feature cliché images of sunsets

on the beach, descending the steps of a private jet, big designer bags, having

a manservant in livery, leopard cushions, party, party, party, and young women

in bikinis. They look sometimes like a Michael Kors

ad. Whether they are to be taken with a grain of salt is irrelevant,

as they are unprotectable scènes

à faire of a “Let’s live in a Jennifer Lopez video”

lifestyle (I love that song).

The case will probably settle (alas, may I

add, rather selfishly).