We have often written on this blog about

the appropriation artist Richard Prince, whose work was at the origin of

several copyright infringement cases, including the Cariou

v. Prince case (see here,

here,

here,

and here).

Copyright bloggers owe him a full bowl of da

la jam gratitude.

Prince is still embroiled in two copyright

infringement suits following his New

Portraits 2014 exhibition at Gagosian

: a copyright infringement suit was filed by photographer Donald Graham (see here)

and another by photographer Eric McNatt (see here),

both in the Southern District of New York (SDNY). These two cases are Eric McNatt v. Richard Prince et al.,

1:16-cv-08896 and Graham v. Prince et al.,

1:15-cv-10160. Richard Prince filed last week his two memorandums of law in

support of his motions for summary judgment in these two cases, see here

and here.

Richard Prince is an appropriation artist.

He explained in his motion to dismiss the McNatt

case that the New Portraits “continue Prince over 40-year

career of using found photos and objects in order to comment on society,

through the use of text and recontextualisation.” The New Portraits, reproductions of Instagram posts complete with a

Prince’s comment, are each approximatively 41 by 41 inches, as an homage to

Andy Warhol who used this format for his portraits, as explained in the McNatt memo.

In the McNatt

case, Prince used a photograph of Kim Gordon, taken by Eric McNatt, and which

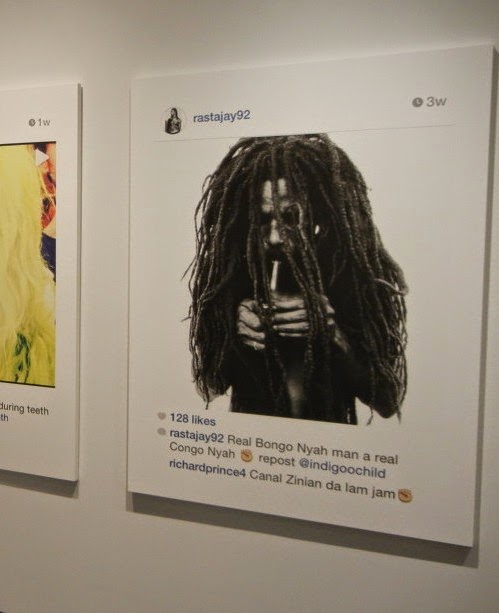

has been published on social media, to create one of his New Portraits works. In the Graham

case, Prince used Graham’s photograph of a

Rastafarian smoking a joint “which

already existed pervasively on the Internet, largely through Donald Graham’s own

actions” according to Prince’s memorandum, to create Portrait of Rastajay92. This is a rather odd argument, as Graham,

as the copyright holder, has the exclusive right to publish his work as he wished

to do, including on the web. This action does not give carte blanche to third parties to copy and use the work without

permission.

Did

Donald Graham grant an implied license?

Prince argued that Donald Graham had

published his work on his Facebook page on a public setting, thus granting

Facebook a non-exclusive, transferable license to use the photograph. Prince

also argued that Graham did not use any embedded watermarks on his work, had

not set any privacy settings for viewing the work, and that he understood that

once published on the web, it was forever published on the web.

Prince argued that he “reasonably interpreted Graham’s conduct as permission to use the [p]hotograph

in a new way” and had a “non-exclusive

implied license” to use the work,

citing the Field

v. Google case from the Nevada district court. In this case, the

court had found that Google had an implied license to display works protected

by copyright in cached links, even though the copyright owner did not

explicitly authorize such use. However, the court noted that Field could have

used a tag directing Google not to archive the pages, but did not do so and

thus had implicitly given Google a license to display his works.

Prince claimed in the McNatt case memo that Eric McNatt and Kim Gordon had posted the

original work on their Instagram accounts, and that McNatt still features the photograph

on his website without embedded watermarks. The original Graham work had been

republished on Instagram by a third party, user Rastajay92, and it is this

social media post which was reproduced by Prince, complete with his own

comment: “Canal Zinian da lam jam,” an

allusion to his Canal

Zone show, or, as Prince puts it, a “self-referential allusio[n] to

his own artistic biography.” I wrote “da

lam jam” on the Google translate box: it detected Arabic as a language, and

offered “it did not g” as a translation.

Curiouser and curiouser!

Prince’s memorandum in the Graham case argues that his New

Portraits exhibition was a “social commentary” and thus a “core

fair use principle… expressed through a novel technological and sociological

medium and context” and that the forfeiture of the works, as asked by

Plaintiff Donald Graham, “would have a

chilling effect on the progress of the arts, to the detriment of the public.”

An

ode to social media

Prince argued that his use of Graham’s work

was highly transformative, because he used what he described as “an austere description of a Rastafarian”

and turned it into “an ode to social media.” Prince further

argued that the fact that he did not add anything to the original work, unlike

in his works in the Cariou case, enhances his fair use claim, not

weakens it, because he needed to “authentically

replicate in the physical world the virtual world of social media.”

He used similar arguments in his motion to

dismiss the McNatt case, that he “imbued what was once an austere depiction, documenting a female rocker in a defiant

pose into part of an ode to social media.“

It may be an ode to social media, but it is

also copyright infringement. The defense is fair use.

Is

this ode to social media fair use?

Prince argued that his New Portraits were a parody of the social media posts as a whole.

So it is an ode to social media which is also a parody. A parody is indeed

highly transformative, and a highly transformative work is likely to be

considered by courts as a fair use of a protected work, under the first fair use

factor.

Prince argued that he used the Kim Gordon

photograph to comment on social media, about “the whole idea of putting up images on a new platform that was

available to anyone, to an entire population” and that artistic purpose was

“a world-away from McNatt’s purpose in making the [p]hotograph.”

For Prince, Graham’s sales of his works

have not suffered because of Prince’s use and Graham’s notoriety has even been

greatly enhanced by Prince’s use, and that thus the fourth fair use factor, the

effect on the market, should weigh in Prince’s favor.

Prince also argued that Graham did not have

the right to exploit the photograph, as the right of publicity of its subject

is governed by Jamaican law, and that therefore any harm done by Prince’s use

of the work would harm an “illegitimate

market.” Prince used a similar argument in his McNatt memo, arguing that the photographer did not obtain Kim

Gordon’s written authorization to use her image, as required by the New York

right of publicity statute, other than for their original use, a publication in

Paper magazine.

Prince also argued that the second

fair use factor, the nature of the copyrighted work, should be in

his favor, as the original Graham work was “more

factual than creative.” As for the third factor, the amount and

substantiality of the work used, in relation to the protected work as a whole,

Prince cited the Bill

Graham case, in both of his memos, where the Second Circuit held

that the third factor can weigh in favor of the defendant even if the work is

reproduced in its entirety.

Prince argued that the original Graham work

has been cropped and that the remaining work was necessary to serve Prince’s

purpose, commenting about social media. He argued in the McNatt memo that Prince used an entire Instagram post, complete

with “colorized emojis” and thus drew

the viewer’s attention around the image, thus “reducing the artistic or intellectual importance of the photographic

image relative to its physical portion of the painting.”

This is quite a fair use battle royal.

Copyrights enthusiasts will keep watching, and possibly, cheering.

Image is courtesy of Flickr user (vincent desjardins)

under a CC BY 2.0 license.