The Court of Justice concurred with the Advocate General's opinion that an artistic work must be capable of being seen and heard. It's the first time the court has been asked to decide whether copyright applies to taste on an artistic work not defined by the InfoSec Directive (Directive 2001/29/EC)

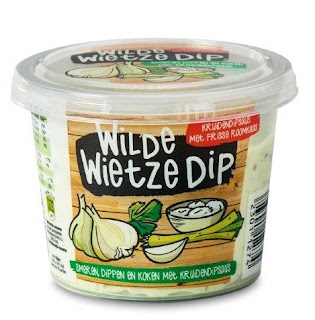

The case was originally filed in the Dutch courts by the owner of the cream cheese brand Heks'nkaas (witches' cheese), Levola Hengelo. Their product is a spreadable cheese with herbs. It objected to a cream cheese, made by rival manufacturer Smilde Foods since 2014 called "Witte Wievenkaas" (wise-women's cheese), which it claimed "infringed" the flavour of Heks'nkaas. Smilde’s herbed cheese dip contains many of the same ingredients. Witte Wievenkaas is now sold under the name Wilde Wietze Dip.

Levola argued that the taste of food, like literary, scientific or artistic works, could be copyrighted, citing the 2006 case involving Lancôme, the cosmetics company, that had accepted in principle that the scent of a perfume could be eligible for copyright protection. Smilde responded that taste is subjective.

The case went on to the appellate court in Arnhem-Leeuwarden which in turn referred the matter to the CJEU for a preliminary ruling.

The upshot of this is the CJEU have found that the taste of a food product is not eligible for copyright protection and the taste of a food product cannot be classified as a ‘work’. In the judgment the Court makes clear that in order to be protected by copyright under the Directive, the taste of a food product must be capable of being classified as a ‘work’ within the meaning of the Directive. Classification as a ‘work’ requires (a) that the subject matter concerned is an original intellectual creation and(b) there must be an ‘expression’ of that original intellectual creation.

In accordance with the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, which was adopted in the framework of the World Trade Organisation and to which the EU has acceded and with the WIPO Copyright Treaty to which the EU is a party, copyright protection may be granted to expressions, but not to ideas, procedures, methods of operation or mathematical concepts as such. Accordingly, for there to be a ‘work’ as referred to in the Directive, the subject matter protected by copyright must be expressed in a manner which makes it identifiable with sufficient precision and objectivity.

In that regard, the Court found that the taste of a food product cannot be identified with precision and objectivity (unlike say a literary, pictorial, cinematographic or musical work, which is a precise and objective expression).: the taste of a food product will be identified essentially on the basis of taste sensations and experiences, which are subjective and variable. They depend on, amongst other things, factors particular to the person tasting the product concerned, such as age, food preferences and consumption habits, as well as on the environment or context in which the product is consumed.

Moreover, it is not possible in the current state of scientific development to achieve by technical means a precise and objective identification of the taste of a food product which enables it to be distinguished from the taste of other products of the same kind.

Accordingly, the Court concludes that the taste of a food product cannot be classified as a ‘work’ and consequently is not eligible for copyright protection under the Directive.

C-310/17 Levola Hengelo BV v Smilde Foods BV

http://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2006/05/article_0001.html