Back in 2016, Hammad Syed and Mahmoud Felfel, an ex-WhatsApp engineer, thought it’d be neat to build a text-to-speech Chrome extension for Medium articles. The extension, which could read any Medium story aloud, was featured on Product Hunt. A year later, it spawned an entire business.

“We saw a bigger opportunity in helping individuals and organizations create realistic audio content for their applications,” Syed told TechCrunch. “Without the need to build their own model, they could deploy human-quality speech experiences faster than ever before.”

Syed and Felfel’s company, PlayAI (formerly PlayHT), pitches itself as the “voice interface of AI.” Customers can choose from a number of predefined voices, or clone a voice, and use PlayAI’s API to integrate text-to-speech into their apps.

Toggles allow users to adjust the intonation, cadence, and tenor of voices.

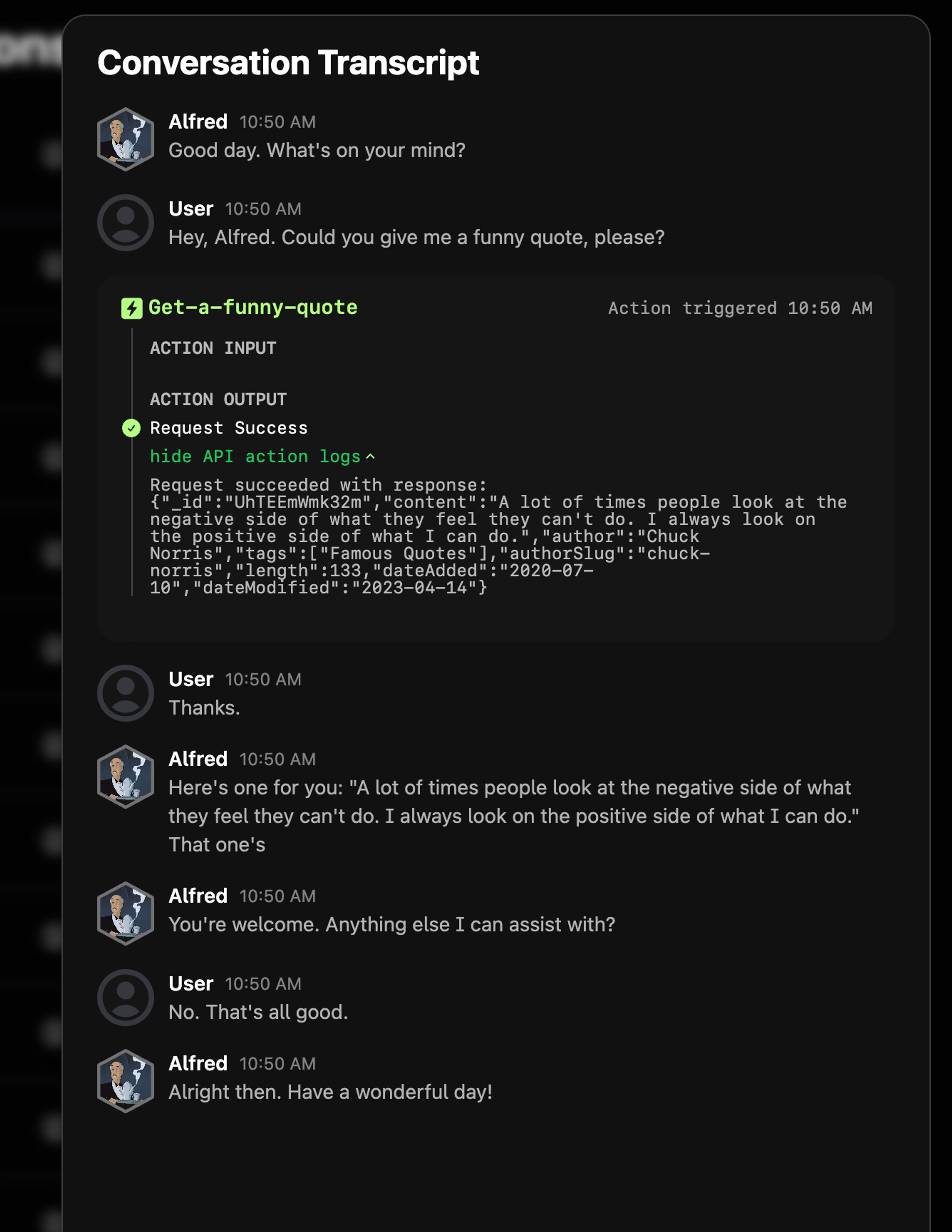

PlayAI also offers a “playground” where users can upload a file to generate a read-aloud version and a dashboard for creating more-polished audio narrations and voice-overs. Recently, the company got into the “AI agents” game with tools that can be used to automate tasks such as answering customer calls at a business.

One of PlayAI’s more interesting experiments is PlayNote, which transforms PDFs, videos, photos, songs, and other files into podcast-style shows, read-aloud summaries, one-on-one debates, and even children’s stories. Like Google’s NotebookLM, PlayNote generates a script from an uploaded file or URL and feeds it to a collection of AI models, which together craft the finished product.

I gave it a whirl, and the results weren’t half bad. PlayNote’s “podcast” setting produces clips more or less on par with NotebookLM’s in terms of quality, and the tool’s ability to ingest photos and videos makes for some fascinating creations. Given a picture of a chicken mole dish I had recently, PlayNote wrote a five-minute podcast script about it. Truly, we are living in the future.

Granted, the tool, like all AI tools, generates odd artifacts and hallucinations from time to time. And while PlayNote will do its best to adapt a file to the format you’ve chosen, don’t expect, say, a dry legal filing to make for the best source material. See: the Musk vs. OpenAI lawsuit framed as a bedtime story:

PlayNote’s podcast format is made possible by PlayAI’s latest model, PlayDialog, which Syed says can use the “context and history” of a conversation to generate speech that reflects the conversation flow. “Using a conversation’s historical context to control prosody, emotion, and pacing, PlayDialog delivers conversation with natural delivery and appropriate tone,” he continued.

PlayAI, which is close rivals with ElevenLabs, has been criticized in the past for its laissez-faire approach to safety. The company’s voice cloning tool requires that users check a box indicating that they “have all the necessary rights or consent” to clone a voice — but there isn’t any enforcement mechanism. I had no trouble creating a clone of Kamala Harris’ voice from a recording.

That’s concerning considering the potential for scams and deepfakes.

PlayAI also claims that it automatically detects and blocks “sexual, offensive, racist, or threatening content.” But that wasn’t the case in my testing. I used the Harris clone to generate speech I frankly can’t embed here and never once saw a warning message.

Meanwhile, PlayNote’s community portal, which is filled with publicly generated content, has files with explicit titles like “Woman Performing Oral Sex.”

Syed tells me that PlayAI responds to reports of voices cloned without consent, like this one, by blocking the user responsible and removing the cloned voice immediately. He also makes the case that PlayAI’s highest-fidelity voice clones, which require 20 minutes of voice samples, are priced higher ($49 per month billed annually or $99 per month) than most scammers are willing to pay.

“PlayAI has several ethical safeguards in place,” Syed said. “We’ve implemented robust mechanisms to identify whether a voice was synthesized using our technology, for example. If any misuse is reported, we promptly verify the origin of the content and take decisive actions to rectify the situation and prevent further ethical violations.”

I’d certainly hope that’s the case — and that PlayAI moves away from marketing campaigns featuring dead tech celebrities. If PlayAI’s moderation isn’t robust, it could face legal challenges in Tennessee, which has a law on the books preventing platforms from hosting AI to make unauthorized recordings of a person’s voice.

PlayAI’s approach to training its voice-cloning AI is also a bit murky. The company won’t reveal where it sourced the data for its models, ostensibly for competitive reasons.

“PlayAI uses mostly open datasets, [as well as licensed data] and proprietary datasets that are built in-house,” Syed said. “We don’t use user data from the products in training, or creators to train models. Our models are trained on millions of hours of real-life human speech, delivering voices in male and female genders across multiple languages and accents.”

Most AI models are trained on public web data — some of which may be copyrighted or under a restrictive license. Many AI vendors argue that the fair-use doctrine shields them from copyright claims. But that hasn’t stopped data owners from filing class action lawsuits alleging that vendors used their data sans permission.

PlayAI hasn’t been sued. However, its terms of service suggest it won’t go to bat for users if they find themselves under legal threat.

Voice cloning platforms like PlayAI face criticism from actors who fear that voice work will eventually be replaced by AI-generated vocals and that actors will have little control over how their digital doubles are used.

The Hollywood actors’ union SAG-AFTRA has struck deals with some startups, including online talent marketplace Narrativ and Replica Studios, for what it describes as “fair” and “ethical” voice cloning arrangements. But even these tie-ups have come under intense scrutiny, including from SAG-AFTRA’s own members.

In California, laws require companies relying on a performer’s digital replica (e.g., cloned voice) give a description of the replica’s intended use and negotiate with the performer’s legal counsel. They also require that entertainment employers gain the consent of a deceased performer’s estate before using a digital clone of that person.

Syed says that PlayAI “guarantees” that every voice clone generated through its platform is exclusive to the creator. “This exclusivity is vital for protecting the creative rights of users,” he added.

The increasing legal burden is one headwind for PlayAI. Another is the competition. Papercup, Deepdub, Acapela, Respeecher, and Voice.ai, as well as Big Tech incumbents Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, offer AI dubbing and voice-cloning tools. The aforementioned ElevenLabs, one of the highest-profile voice-cloning vendors, is said to be raising new funds at a valuation over $3 billion.

PlayAI isn’t struggling to find investors, though. This month, the Y Combinator-backed company closed a $21 million seed round co-led by 500 Startups and Kindred Ventures with participation from Race Capital, 500 Global, and Soma Capital.

“The new capital will be used to invest in our generative AI voice models and voice agent platform, and to shorten the time for businesses to build human-quality speech experiences,” Syed said, adding that PlayAI plans to expand its 40-person workforce.