February 5, 2025 feature

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

New evidence suggests Funerary Palaces in the southern Levant originated in the north

A study published by Dr Holly Winter in the journal Levant investigated the potential origin of Funerary Palaces in the southern Levant. Using various pieces of evidence, including architectural similarities, association with tombs or burials, and artifact similarities, she hypothesizes that southern Levantine Funerary Palaces may actually have their origin in the northern Levant, from where they gradually spread south.

"I was interested in understanding where the phenomenon of the southern Levantine palaces originated," she explains.

"In general, palace studies of the Middle Bronze Age, palaces of the north and south Levant differ drastically in size and elaboration. However, at the start of the Middle Bronze Age, a lot was changing and developing, with influence from the northern Levant recognized in culture, society, and politics."

Looking north proved fruitful: "By looking to the northern Levant, there were clear examples that appeared to follow the template that I had started to recognize for the southern Levantine Funerary Palaces, and so I decided to follow this line of inquiry."

Dr Winter elaborates on this line of thought, saying, "People did not acknowledge the primary funerary connection in the Courtyard Palaces (now referred to as Funerary Palaces), and this hindered comparisons with the north, which were admittedly much larger and more varied."

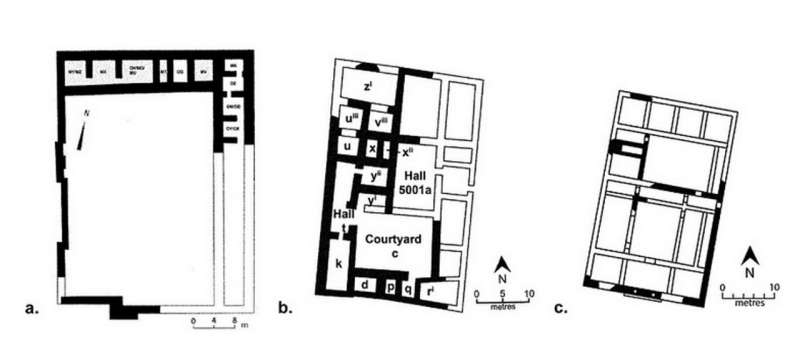

During the Middle Bronze Age (ca. 2000–1500 BCE), Funerary Palaces were a key feature of southern Levantine society. They were characterized by their monumental size (up to 50 m long, 30–40 m wide), north-south orientation, location atop hills or acropolises, and composition of multiple satellite rooms usually centered around one or more central courtyards.

They were built atop sandstone foundations and mudbrick superstructures, typically enclosed in a bounding wall. Unlike other palaces in the northern and southern Levant, funerary palace rooms are typically relatively empty, and the few artifacts found within them usually have a funerary function.

The lack of artifacts is consistent with the cleanliness associated with ritual practices and is generally similar to temples at the time, and unlikely to have been the result of looting, says Dr. Winter.

"While we cannot discount that looting in antiquity may account for the lack of valuable burial goods and items in these Funerary Palace structures, I think the fact that all these buildings experience the same emptiness is too coincidental to be attributed to later robbing events. I think the items we do find are telling of the burial practices of the time, hinting at how the Funerary Palaces functioned."

One of the possibly oldest Funerary Palaces is located in Ebla (Tell Mardikh), around 60 km southwest of Aleppo in Syria. It was built around the Middle Bronze (MB) I (2000–1800 BC) and remained in use until its destruction around the MB II 1600 BC.

It consists of two structures, the Western Palace and the Royal Necropolis. The Western Palace is a large structure made up of 17 satellite and 25 internal courtyard rooms.

Artifacts within are scarce and consist mainly of 16 basalt grindstones and pestles, jars containing cylinder seal impressions, and a bowl with two cuneiform tablets; additional finds include a basalt statue base showing two lion heads flanking a royal figure with a defeated enemy in a net below his feet, a lion-shaped weight, and a ceramic horseshoe-shaped piece (possibly a small oven).

On one of the cuneiform tablets was the name of one of the last kings of Ebla during the MB II, Indilimgur.

The Western Palace likely served as a residence for the Crown Prince, whose role was to facilitate the funerary practices associated with the royal ancestral cult.

Beneath the Western Palace, the Royal Necropolis was located. It was a burial ground likely reserved for royal or elite individuals of Ebla. The series of tombs included a rich funerary assemblage consisting of jewelry, beads, ceramic vessels, alabaster, bronze, weapons, silver and gold items, two pharaonic scepters, and a silver bowl inscribed with the royal name "Immeya."

The Funerary Palace's foreign objects indicate Ebla was likely in commercial contact with other cultural centers, including various regions in the south.

Hoping to find a link between Ebla's Funerary Palace and southern Levantine ones, Funerary Palaces found between the two regions were compared.

Dr. Winter found that Funerary Palaces in Byblos and Tell el-Burak, which were both major centers of commerce situated south of Ebla along the coast, had similar Funerary Palaces.

In fact, while many Funerary Palaces in the southern Levant had mainly been compared solely based on their architectural similarities, the Ebla Funerary Palace and the ones at Byblos and Tell el-Burak shared not only architectural features but the tombs and artifacts within them were also all broadly similar and contemporary to one another.

These included gold twisted wire bracelets from Tomb II at Byblos and the Tomb of the Princess at Ebla, beads with thickened edges and fine thread found in both Byblos's Tomb III and Ebla's Tomb of the Lord of the Goats, and similar architectural designs featuring plastering, satellite rooms and central courtyards between the sites.

Since Ebla's Funerary Palace is among the oldest, it stands to reason that the tradition of Funerary Palaces may have originated in the north, like in Ebla, and spread along the cities of Byblos and Tell el-Burak, which were also sites of major commerce.

Dr. Winter hypothesizes that these more southerly situated cities, with ties to the southern Levant, served as waypoints at which traditions and cultural ideas from the north could flow southward. This includes the Funerary Palace tradition before they developed into more distinct versions of the northern palaces.

More information: Holly A. Winter, Ancestral origins: northern Levantine Funerary Palaces in the Middle Bronze Age, Levant (2024). DOI: 10.1080/00758914.2024.2414580.

© 2025 Science X Network