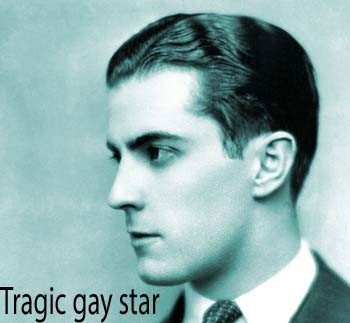

“Latin Lover” Ricardo Cortez, who went on to play a series of all-American scoundrels and criminals, in addition to similar unsavory types of other nationalities. Although never as big a star as fellow silent era screen heartthrobs Rudolph Valentino, Ramon Novarro, and John Gilbert – or fellow Pre-Code era antiheroes Edward G. Robinson and James Cagney – Cortez had a long and, to some extent, prestigious film career, appearing in nearly 100 movies between 1923 and 1950. Among his directors were “Father of American Cinema” D.W. Griffith and Paramount’s star filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille, in addition to eventual Oscar winners and nominees Frank Lloyd, Herbert Brenon, Gregory La Cava, William A. Wellman, Frank Capra, Walter Lang, Michael Curtiz, John Ford, and Alexander Hall. Also: Allan Dwan, James Cruze, Alexander Korda, Roy Del Ruth, Lloyd Bacon, Tay Garnett, Archie Mayo, and Raoul Walsh.

“Latin Lover” Ricardo Cortez, who went on to play a series of all-American scoundrels and criminals, in addition to similar unsavory types of other nationalities. Although never as big a star as fellow silent era screen heartthrobs Rudolph Valentino, Ramon Novarro, and John Gilbert – or fellow Pre-Code era antiheroes Edward G. Robinson and James Cagney – Cortez had a long and, to some extent, prestigious film career, appearing in nearly 100 movies between 1923 and 1950. Among his directors were “Father of American Cinema” D.W. Griffith and Paramount’s star filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille, in addition to eventual Oscar winners and nominees Frank Lloyd, Herbert Brenon, Gregory La Cava, William A. Wellman, Frank Capra, Walter Lang, Michael Curtiz, John Ford, and Alexander Hall. Also: Allan Dwan, James Cruze, Alexander Korda, Roy Del Ruth, Lloyd Bacon, Tay Garnett, Archie Mayo, and Raoul Walsh.

Ricardo Cortez: Biographer Dan Van Neste discusses Paramount’s ‘Latin Lover’ threat to Rudolph Valentino

See introductory post: “Remembering Ricardo Cortez: Latin Lover ‘Threat’ to Rudolph Valentino & Star of the Original The Maltese Falcon.”

Below is Part I of a three-part interview with Ricardo Cortez biographer Dan Van Neste.

- First of all, why a biography of the 1920s “Latin Lover” and 1930s scoundrel Ricardo Cortez?

Since I began writing about classic movies and vintage filmmakers roughly 30 years ago, people have always been curious why I choose particular subjects. It sounds kind of corny, but I have always wanted to do original work and perhaps make a minor contribution to film history at the same time.

Many fine biographical books have been written chronicling the lives and careers of the more famous actors and filmmakers of classic cinema, but most of the lesser stars (second leads, character players who also made significant contributions) have been ignored. I believe their stories should also be told.

To me, Ricardo Cortez was the perfect subject. He was a popular and extremely charismatic actor of the late silent and early sound eras, appeared in over 100 feature films, was the only star billed over Greta Garbo, the first to play Sam Spade [in the 1931 version of The Maltese Falcon], worked with most of the legendary filmmakers of his time, yet almost nothing has been written about his life and career. I feel very honored to have had the opportunity to recount his colorful life story.

The Spaniard with Latin Lover Ricardo Cortez. Three years after Rudolph Valentino starred as a bullfighter in Fred Niblo’s 1922 film version of Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s Blood and Sand, Famous Players-Lasky (later reorganized under the name of its distribution arm, Paramount) cast the former Jacob Krantz of Manhattan as Don Pedro de Barrego in Raoul Walsh’s The Spaniard – Cortez’s first official starring role and one of a number of Spanish-named characters he got to play during the silent era. Dutch-born actress Jetta Goudal was the reticent Englishwoman with whom Don Pedro falls passionately – “’The woman does not exist whom I cannot tame!’ boasts the Spaniard” – in love.

The Spaniard with Latin Lover Ricardo Cortez. Three years after Rudolph Valentino starred as a bullfighter in Fred Niblo’s 1922 film version of Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s Blood and Sand, Famous Players-Lasky (later reorganized under the name of its distribution arm, Paramount) cast the former Jacob Krantz of Manhattan as Don Pedro de Barrego in Raoul Walsh’s The Spaniard – Cortez’s first official starring role and one of a number of Spanish-named characters he got to play during the silent era. Dutch-born actress Jetta Goudal was the reticent Englishwoman with whom Don Pedro falls passionately – “’The woman does not exist whom I cannot tame!’ boasts the Spaniard” – in love.

The original Latin Lover from Manhattan

- In The Magnificent Heel you discuss Jacob Krantz’s transformation into potential Rudolph Valentino rival Ricardo Cortez. In brief, how did that come about? And what did Cortez, the son of Austrian/Hungarian Jewish parents, think of being sold as a “Latin Lover”?

In essence, Ricardo Cortez owed his career to Valentino. If Rudy had never existed, it’s highly doubtful Cortez would ever have won a studio contract or achieved success in films even though he was talented, ambitious, and very determined. Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount discovered and promoted Cortez, the former Manhattan-born Jacob Krantz, essentially as an insurance policy. Let me explain.

When the young Cortez was signed to a contract in 1922, Rudolph Valentino was at the height of his fame, the studio’s most popular male star. He had made several critically acclaimed hit motion pictures which established him as the cinema’s “Latin Lover,” a fantasy man to all the young female filmgoers who flocked to theatres to see him.

In spite of his success at Paramount, Valentino was becoming restless there, expressing dissatisfaction with the scripts he was assigned, and demanding more creative control. When Paramount resisted, Rudy embarked on a “one-man strike.” Young Krantz (who strongly resembled Rudy) was signed to a long-term Paramount contract in case Valentino became too hard to handle.

After giving the young man a new “Latin-sounding” name, Ricardo Cortez (concocted by Jesse L. Lasky and his secretary), and a new phony biography (which had the poor, Manhattan-born son of immigrants as a member of the European aristocracy), Lasky and company immediately set about promoting their discovery as a rival to Rudy in photo shoots and by assigning him several “Valentino-esque” parts in pictures like The Next Corner (1924), Argentine Love (1924), and The Spaniard (1925).

Cortez was extremely uncomfortable with this. He was proud of his roots, loved his parents, and was saddened he was forced to renounce his Jewish heritage – but he had worked for years as a bit player to achieve a major breakthrough in the movies. He was so grateful to be given this opportunity, he cooperated with the studio’s schemes.

At the same time, he was wise enough to realize that copying someone else was not a recipe for long-term success. Throughout the early years of his career, he continually strived to demonstrate his acting versatility and to escape Rudy’s shadow.

Wonder Bar (1934) with Ricardo Cortez and Dolores Del Rio. Like the screen’s Latin Lover Cortez, Del Rio played numerous foreigners – “exotic” or otherwise – during the silent era (e.g., Ramona, Resurrection, The Loves of Carmen). Unlike Cortez, Del Rio, born in Durango, Mexico, had at least some Spanish background in real life. Also unlike Cortez, the Mexican-accented Del Rio went on playing foreigners in Hollywood talkies, including her Inez to Cortez’s heel-ish Harry in Wonder Bar, Lloyd Bacon’s pre-Production Code mix of melodrama, music, and murder, costarring Al Jolson, Kay Francis, and Dick Powell. And, again, unlike Cortez, Dolores Del Rio would manage to make a sensational film comeback, eventually becoming a national icon in her native Mexico while making sporadic trips back to Hollywood well into the 1960s.

Second-string Valentino & second-rate Sam Spade?

- In the introduction to The Magnificent Heel, you explain that Ricardo Cortez has often been dismissed as “a second string Valentino or a second rate Sam Spade.” Is that in any way a fair assessment of his talent as an actor? To whatever degree, did Cortez, like screen lovers such as Rudolph Valentino and John Gilbert, leave his mark in the movies of the 1920s (or 1930s)?

I discuss these issues in great specificity in the book. Let me take this opportunity to share a few important details about The Magnificent Heel.

It is divided into two parts. Part I is a biography and Part II is a detailed filmography. In the introduction, I set forth three basic questions I hoped to answer in the book. They were: Who was Ricardo Cortez? Why has he been forgotten? What is his true legacy?

In search of answers to those questions, readers are taken on a journey inside Cortez’s world, from his poverty-stricken beginnings in turn of the century New York City, through his topsy-turvy years in Hollywood, then later back to New York. They encounter all the colorful people and the circumstances that shaped and influenced his life, and hopefully see how and why he became the person he was and made the decisions he made.

I purposely added a 12th chapter to the biography section, titled “Ricardo Cortez, One Author’s View,” in order to provide answers to the above questions. In Chapter Twelve, I offer my impressions and opinions of Cortez both personally and professionally, attempt to address the reasons for his obscurity, and assess his overall legacy.

I must admit a little bit of irritation with those who completely dismiss Cortez’s ability, and refer to him as “second rate.” Everyone is entitled to their viewpoint, but I do believe such opinions are grossly unfair, and many of these assessments are based on very limited knowledge of Cortez’s work in the movies. While I would certainly not rank him among the very greatest actors of the silver screen, his various achievements, the length of his career, the variety of the roles he played, and the great reviews he received from even the toughest critics should stand for something.

It is true he is not as historically important or influential as Valentino or Gilbert, but I do believe Cortez left his mark, and deserves to be remembered. In addition to the reasons I cited above, I feel Cortez was a particularly significant actor of the Pre-Code era (1930–34) – a brief, fascinating period in film history between the advent of sound and the institution of excessive censorship measures associated with the strict enforcement of the Production Code in 1934.

During these years, filmmakers were allowed relative freedom to present mature, sophisticated themes in an adult manner. Ricardo Cortez reached the pinnacle of his popularity during this period, often playing heels and villains – lascivious, opportunistic, often violent characters.

The freedom enjoyed by filmmakers at the time essentially enhanced Cortez’s performances, allowing his portrayals of these characters to be more colorful and realistic. He brought a multi-dimensional depth to these characterizations which made them at once appealing yet despicable! There were other actors who played this type of role, but few were as convincing.

I am reminded of a humorous review of the melodramatic film Mandalay (1934), penned by Andre Sennwald in the New York Times. In the film (which was released before the strict Code enforcement), Cortez portrayed a charming, yet totally corrupt gun runner who sells his girlfriend (Kay Francis) into white slavery to pay off a debt.

Sennwald did not particularly like the film, but was mesmerized by Cortez’s performance. He said, “Ricardo Cortez generates so much sympathy as the villain, that his demise removes the one character for whom the audience feels anything like affection.”

Ricardo Cortez in Mandalay, making love to Kay Francis – not long before he sells her into the “white slave trade,” in which Francis reaches the top of her profession as a lavishly garbed Rangoon nightclub hostess known as “Spot White.” Whether in Burma or elsewhere, Cortez was featured opposite a whole array of female stars during both the silent and the talkie eras. Earlier on, plots usually revolved around his – generally speaking – heroic characters; later on, plots usually revolved around the characters of his invariably victimized-but-heroic leading ladies, with the former Latin Lover cast as a heel of varying degrees of egotism. Besides Mandalay, Ricardo Cortez and Kay Francis were featured together in Transgression, The House on 56th Street, and Wonder Bar. Somehow or other, their screen partnership worked for Francis; less so for Cortez, who ended up a corpse in every single one of these titles.

Ricardo Cortez in Mandalay, making love to Kay Francis – not long before he sells her into the “white slave trade,” in which Francis reaches the top of her profession as a lavishly garbed Rangoon nightclub hostess known as “Spot White.” Whether in Burma or elsewhere, Cortez was featured opposite a whole array of female stars during both the silent and the talkie eras. Earlier on, plots usually revolved around his – generally speaking – heroic characters; later on, plots usually revolved around the characters of his invariably victimized-but-heroic leading ladies, with the former Latin Lover cast as a heel of varying degrees of egotism. Besides Mandalay, Ricardo Cortez and Kay Francis were featured together in Transgression, The House on 56th Street, and Wonder Bar. Somehow or other, their screen partnership worked for Francis; less so for Cortez, who ended up a corpse in every single one of these titles.

Character transformation following sound revolution

- How smooth was Ricardo Cortez’s transition to sound? Did he have to alter his Latin Lover film persona/acting style to fit the more naturalistic talkie era? If so, would you say he succeeded in tailoring his performances to the new medium?

Although he did ultimately achieve his greatest success in the new sound era, Cortez’s transition from silents to sound should have been a bit easier than it turned out to be. He possessed a pleasant-sounding baritone speaking voice, but after the sound revolution Hollywood producers appeared biased against former silent screen stars in favor of Broadway actors who possessed stage-trained voices.

In order to continue his film acting career, Cortez was forced to prove his vocal and acting ability by doing a vaudeville stint, and by completely changing his screen persona from largely heroic roles to villains. His versatility and ability to adapt were severely tested at this time, but the fact that he was able to make a successful transition – when so many other silent stars were not – was impressive.

The Maltese Falcon 1931: Ricardo Cortez and Bebe Daniels star as the characters incarnated by Humphrey Bogart and Mary Astor in John Huston’s widely acclaimed, Academy Award-nominated, 1941 film noir. A light, racy, fast-paced, remarkably enjoyable – and unfairly neglected – version of Dashiell Hammett’s 1930 novel, Roy Del Ruth’s Pre-Code talkie features Cortez at his very best. Coincidentally, The Maltese Falcon 1941 leading lady Mary Astor and Ricardo Cortez were featured together in six movies: Behind Office Doors (1931), Men of Chance (1931), White Shoulders (1931), I Am a Thief (1934), The Man with Two Faces (1934), and The Murder of Dr. Harrigan (1936). Next time it’s aired: on television, The Maltese Falcon 1931 is known as Dangerous Female.

The Maltese Falcon 1931: Ricardo Cortez and Bebe Daniels star as the characters incarnated by Humphrey Bogart and Mary Astor in John Huston’s widely acclaimed, Academy Award-nominated, 1941 film noir. A light, racy, fast-paced, remarkably enjoyable – and unfairly neglected – version of Dashiell Hammett’s 1930 novel, Roy Del Ruth’s Pre-Code talkie features Cortez at his very best. Coincidentally, The Maltese Falcon 1941 leading lady Mary Astor and Ricardo Cortez were featured together in six movies: Behind Office Doors (1931), Men of Chance (1931), White Shoulders (1931), I Am a Thief (1934), The Man with Two Faces (1934), and The Murder of Dr. Harrigan (1936). Next time it’s aired: on television, The Maltese Falcon 1931 is known as Dangerous Female.

From Latin Lover to hard-boiled sleuth: Ricardo Cortez as Sam Spade

- How successful was Roy Del Ruth’s 1931 The Maltese Falcon? Why didn’t that lead to more such roles – and movies – for Ricardo Cortez? In your view, how does the Del Ruth-Cortez collaboration compare to the acclaimed John Huston-Humphrey Bogart version?

I could write a book on this topic alone! First, let me make this clear. In my opinion, director John Huston’s 1941 adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s classic crime story The Maltese Falcon is the definitive one! Huston crafted one of the greatest classics of the silver screen with one of the best casts ever assembled, including the great Bogart as Spade. I am a huge fan of that motion picture.

Roy Del Ruth’s original 1931 film adaptation of the Hammett story is inferior in several respects. In my opinion, the supporting cast is not as good, the movie has a certain “stagy” quality, suffers from sound deficiencies, lacks a musical score, etc.

With all that said, I nevertheless believe Del Ruth’s The Maltese Falcon to be an extremely enjoyable, frequently compelling motion picture. With its combination of mystery, intrigue, humor, sex, and romance, it is 80 minutes of excellent Pre-Code entertainment which seems to improve with each viewing.

Huston’s version improved on the original, but he was undoubtedly influenced by the 1931 version and copied several scenes. In recent years, Del Ruth’s The Maltese Falcon, also known by its television title, Dangerous Female, has developed an increasingly large and devoted following.

I strongly disagree with those who claim the movie was a bomb and Cortez’s portrayal of Spade “second rate.” Certainly critics and filmgoers did not feel that way when the movie was released. It was an enormous critical and box office smash.

The Maltese Falcon with Ricardo Cortez as Sam Spade. The former Latin Lover could have become a great film noir star, had he been around – as a bankable leading man – a decade after the original Hollywood adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s mystery novel came out. In-between the 1931 and 1941 versions, there was also a now largely forgotten 1936 version of the same story, Satan Met a Lady, directed by William Dieterle, and starring Bette Davis, Warren William, and Alison Skipworth as Madame Barabbas – a cross-gender take on the role played by Dudley Digges and Sydney Greenstreet in, respectively, the 1931 and 1941 movies.

The Maltese Falcon with Ricardo Cortez as Sam Spade. The former Latin Lover could have become a great film noir star, had he been around – as a bankable leading man – a decade after the original Hollywood adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s mystery novel came out. In-between the 1931 and 1941 versions, there was also a now largely forgotten 1936 version of the same story, Satan Met a Lady, directed by William Dieterle, and starring Bette Davis, Warren William, and Alison Skipworth as Madame Barabbas – a cross-gender take on the role played by Dudley Digges and Sydney Greenstreet in, respectively, the 1931 and 1941 movies.

Regarding Cortez as Spade, I’ll just say this. He played the role as written. The complete story of the production of Del Ruth’s The Maltese Falcon is told in The Magnificent Heel, including many fascinating behind-the-scenes details about the filming and the evolution of the film’s script.

According to archival records (kept at the Warner Brothers Archives, University of Southern California), the screenplay was revised several times. The last time it was redone, the emphasis was placed on the Ruth Wonderly character to be portrayed by Bebe Daniels (who had recently signed a contract with Warners and was to receive top billing). The sexy relationship between Spade and Wonderly was enhanced in the latter version.

Cortez was borrowed from RKO at the last minute to play Spade. According to the final script, Spade (now essentially a subordinate character) was to be an amoral, opportunistic womanizer. That is exactly how Ricardo portrayed him.

Much to the surprise of studio executives, who had envisioned the film as a Daniels vehicle, Ricardo’s Spade dominated the film and wowed the critics. The studio was so pleased with his work they began planning a sequel, but Cortez was an RKO contract player at the time, and the deal was never finalized.

One more thing. In response to those who say Cortez misinterpreted the part, or say he wasn’t a good enough actor to carry it off, in the book I included a very interesting testimonial to Cortez’ portrayal which I was surprised to find in the archival records. It was written by the ultimate authority, none other than the author Dashiell Hammett.

“’Latin Lover’ Ricardo Cortez: Biographer Dan Van Neste Discusses the Second Valentino & First Sam Spade” follow-up post: “How to Be a Latin Lover: Ricardo Cortez & Leading Ladies + Marriage to Tragic Drug-Addicted Hollywood Star.”

The Magnificent Heel: The Life and Films of Ricardo Cortez at amazon.com.

Latin Lover Ricardo Cortez image: Famous Players-Lasky / Paramount publicity shot ca. 1925.

Image of Latin Lover Ricardo Cortez in The Spaniard: Famous Players-Lasky / Paramount.

Dolores Del Rio and – by then former Latin Lover – Ricardo Cortez Wonder Bar image: Warner Bros.

Kay Francis and Ricardo Cortez Mandalay image: Warner Bros.

Images of Bebe Daniels and Latin Lover turned sensual sleuth Ricardo Cortez in The Maltese Falcon: Warner Bros.