| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

Anticontrarianism

Bayes, Anti-Bayes

Biology

Commit a Social Science

Complexity

Corrupting the Young

Creationism

Cthulhiana

Dialogues

Enigmas of Chance

Food

Friday Cat Blogging

Heard About Pittsburgh, PA

IQ

Islam

Kith and Kin

Learned Folly

Linkage

Mathematics

Minds, Brains, and Neurons

Modest Proposals

Networks

Philosophy

Physics

Pleasures of Detection, Portraits of Crime

Postcards

Power Laws

Psychoceramica

Scientifiction and Fantastica

Self-Centered

The Beloved Republic

The Collective Use and Evolution of Concepts

The Commonwealth of Letters

The Continuing Crises

The Dismal Science

The Eternal Silence of These Infinite Spaces

The Great Transformation

The Natural Science of the Human Species

The Progressive Forces

The Running-Dogs of Reaction

Writing for Antiquity

Professorial homepage

News and Blogroll

Research

Notebooks

My books (LibraryThing)

Buy me more books! (wishlist)

pinboard (bookmarks)

tumblr (images)

flickr (snapshots)

- Palani Mohan, Hunting with Eagles: In the Realm of the Mongolian Kazakhs

- Beautiful black-and-white photographs of, as it says, Mongolian Kazakhs hunting with eagles, and their landscape. Many of them are just stunningly composed.

- Statistics Department, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, 13--17 and 20--22 March 2017

- A short course on "Nonparametric tools for statistical network modeling", based on 36-781.

- Santa Fe Institute, Complex Systems Summer School, 20--21 June 2017

- Exact dates tentative.

April 22, 2025

Course Announcement: "Statistical Principles of Generative AI" (Fall 2025)

Attention conservation notice: Notice of a fairly advanced course in a discipline you don't study at a university you don't attend. Combines a trendy subject matter near the peak of its hype cycle with a stodgy, even resentful, focus on old ideas.

This fall will be the beginning of my 21st year at CMU. I should know better than to volunteer to do a new prep --- but I don't.

- Special Topics in Statistics: Statistical Principles of Generative AI (36-473/36-673)

- Description: Generative artificial intelligence systems are

fundamentally statistical models of text and images. The systems are

very new, but they rely on well-established ideas about modeling and

inference, some of them more than a century old. This course will

introduce students to the statistical underpinnings of large language

models and image generation models, emphasizing high-level principles

over implementation details. It will also examine controversies about

generative AI, especially the "artificial general intelligence" versus

"cultural technology" debate, in light of those statistical

foundations.

- Audience: Advanced undergraduates in statistics and closely related majors; MS students in statistics.

- Pre-requisites: 36-402 for undergraduates taking 36-473. For MS students taking 36-473, preparation equivalent to 36-402 and all its pre-req courses in statistics and mathematics. A course in stochastic processes, such as 36-410, is helpful but not required.

- Expectations: All students can expect to do math, a lot of reading (not just skimming of AI-generated summaries) and writing, and do some small, desktop-or-laptop-scale programming exercises. Graduate students taking 36-673 will do small-group projects in the second half of the semester, which will require more elaborate programming and data analysis (and, probably, the use of departmental / university computing resources).

- Time and place: Tuesdays and Thursdays, 2:00--3:20 pm, Baker Hall A36

- Topical outline (tentative): Data compression and generative modeling; probability, likelihood, perplexity, and information. Large language models are high-order parametric Markov models fit by maximum likelihood. First-order Markov models and their dynamics. Estimating parametric Markov models by maximum likelihood and its asymptotics. Influence functions for Markov model estimation. Back-propagation for automatic differentiation. Stochastic gradient descent and other forms of stochastic approximation. Estimation and dynamics for higher-order Markov models. Variable-length Markov chains and order selection; parametric higher-order Markov chains. Prompting as conditioning. Influence functions and source attribution. Transformers; embedding discrete symbols into continuous vector spaces. Identification issues with embeddings; symmetries and optimization. "Attention", a.k.a. kernel smoothing. State-space modeling. Generative diffusion models. Diffusion as a stochastic (Markov) process; a small amount of stochastic calculus. Learning to undo diffusion. Mixture models. Generative diffusion models vs. kernel density estimation. Information-theoretic methods for diffusion density estimation. Combining models of text and images. Prompting as conditioning, again.

- Audience: Advanced undergraduates in statistics and closely related majors; MS students in statistics.

All of this, especially the topical outline, is subject to revision as we get closer to the semester actually starting.

Posted at April 22, 2025 12:55 | permanent link

April 21, 2025

Data Over Space and Time

Collecting posts related to this course (36-3467/36-667).

- Fall 2018:

- Books to Read While the Algae Grow in Your Fur, June 2018

- Course Announcement

- Lecture 1: Introduction to the Course

- Lectures 2 and 3: Smoothing, Trends, Detrending

- Lecture 4: Principal Components Analysis I

- Lecture 5: Principal Components Analysis II

- Lecture 6: Optimal Linear Prediction

- Lecture 7: Linear Prediction for Time Series

- Lecture 8: Linear Prediction for Spatial and Spatio-Temporal Random Fields

- Lectures 9--13: Filtering, Fourier Analysis, African Population and Slavery, Linear Generative Models

- Lectures 14 and 15: Inference for Dependent Data

- Lecture 17: Simulation

- Lectures 18 and 19: Simulation for Inference

- Lecture 20: Markov Chains

- Lectures 21--24: Compartment Models, Optimal Prediction, Inference for Markov Models, Markov Random Fields, Hidden Markov Models

- Self-Evaluation and Lessons Learned

- Books to Read While the Algae Grow in Your Fur, December 2018

- Books to Read While the Algae Grow in Your Fur, January 2019

- Books to Read While the Algae Grow in Your Fur, February 2019

- Fall 2020 (inshallah):

Posted at April 21, 2025 21:17 | permanent link

The Distortion Is Inherent in the Signal

Attention conservation notice: An overly-long blog comment, at the unhappy intersection of political theory and hand-wavy social network theory.

Henry Farrell has a recent post on how "We're getting the social media crisis wrong". I think it's pretty much on target --- it'd be surprising if I didn't! --- so I want to encourage my readers to become its readers. (Assuming I still have any readers.) But I also want to improve on it. What follows could have just been a comment on Henry's post, but I'll post it here because I feel like pretending it's 2010.

Let me begin by massively compressing Henry's argument. (Again, you should read him, he's clear and persuasive, but just in case...) The real bad thing about actually-existing social media is not that it circulates falsehoods and lies. Rather it's that it "creates publics with malformed collective understandings". Public opinion doesn't just float around like a glowing cloud (ALL HAIL) rising nimbus-like from the populace. Rather, "we rely on a variety of representative technologies to make the public visible, in more or less imperfect ways". Those technologies shape public opinion. One way in particular they can shape public opinion is by creating and/or maintaining "reflective beliefs", lying somewhere on the spectrum between cant/shibboleths and things-you're-sure-someone-understands-even-if-you-don't. (As an heir of the French Enlightenment, many of Dan Sperber's original examples of such "reflective beliefs" concerned Catholic dogmas like trans-substantiation; I will more neutrally say that I have a reflective belief that botanists can distinguish between alders and poplars, but don't ask me which tree is which.) Now, at this point, Henry references a 2019 article in Logic magazine rejoicing in the title "My Stepdad's Huge Data Set", and specifically the way it distinguishes between those who merely consume Internet porn, and the customers who actually fork over money, who "convert". To quote the article: "Porn companies, when trying to figure out what people want, focus on the customers who convert. It's their tastes that set the tone for professionally produced content and the industry as a whole." To quote Henry: "The result is that particular taboos ... feature heavily in the presentation of Internet porn, not because they are the most popular among consumers, but because they are more likely to convert into paying customers. This, in turn, gives porn consumers, including teenagers, a highly distorted understanding of what other people want and expect from sex, that some of them then act on...."

To continue quoting Henry:

Something like this explains the main consequences of social media for politics. The collective perspectives that emerge from social media --- our understanding of what the public is and wants --- are similarly shaped by algorithms that select on some aspects of the public, while sidelining others. And we tend to orient ourselves towards that understanding, through a mixture of reflective beliefs, conformity with shibboleths, and revised understandings of coalitional politics.

At this point, Henry goes on to contemplate some recent grotesqueries from Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg. Stipulating that those are, indeed, grotesque, I do not think they get at the essence of the problem Henry's identified, which I think is rather more structural than a couple of mentally-imploding plutocrats. Let me try to lay this out sequentially.

- The distribution of output (number of posts) etc. over users is strongly right-skewed. Even if everyone's content is equally engaging, and equally likely to be encountered, this will lead to a small minority having a really disproportionate impact on what people perceive in their feeds.

- Connectivity is also strongly right-skewed. This is somewhat

endogenous to algorithmic choices on the part of

social-media system operators, but not entirely.

(One algorithmic choice is to make "follows" an asymmetric relationship. [Of course, the fact that the "pays attention to" relationship is asymmetric has been a source of jokes and drama since time out of mind, so maybe that's natural.] Another is to make acquiring followers cheap, or even free. If people had to type out the username of everyone they wanted to see a post, every time they posted, very few of us would maintain even a hundred followers, if that.) - Volume of output, and connectivity, are at the very least not negatively associated. (I'd be astonished if they're not positively associated but I can't immediately lay hands on relevant figures.) *

- People who write a lot are weird. As a sub-population, we are, let us say, enriched for those who are obsessed with niche interests. (I very much include myself in this category.) This of course continues Henry's analogy to porn; "Proof is left as an exercise for the reader's killfile", as we used to say on Usenet. **

- Consequence: even if the owners of the systems didn't put their thumbs on the scales, what people see in their feeds would tend to reflect the pre-occupations of a comparatively small number of weirdos. Henry's points about distorted collective understandings follow.

Conclusion: Social media is a machine for "creat[ing] publics with malformed collective understandings".

The only way I can see to avoid reaching this end-point is if what we prolific weirdos write about tends to be a matter of deep indifference to almost everyone else. I'd contend that in a world of hate-following, outrage-bait and lolcows, that's not very plausible. I have not done justice to Henry's discussion of the coalitional aspects of all this, but suffice it to say that reflective beliefs are often reactive, we're-not-like-them beliefs, and that people are very sensitive to cues as to which socio-political coalition's output they are seeing. (They may not always be accurate in those inferences, but they definitely draw them ***.) Hence I do not think much of this escape route.

--- I have sometimes fantasized about a world where social media are banned, but people are allowed to e-mail snapshots and short letters to their family and friends. (The world would, un-ironically, be better off if more people were showing off pictures of their lunch, as opposed to meme-ing each other into contagious hysterias.) Since, however, the technology of the mailing list with automated sign-on dates back to the 1980s, and the argument above says that it alone would be enough to create distorted publics, I fear this is another case where Actually, "Dr. Internet" Is the Name of the Monsters' Creator.

(Beyond all this, we know that the people who use social media are not representative of the population-at-large. [ObCitationOfKithAndKin: Malik, Bias and Beyond in Digital Trace Data.] For that matter, at least in the early stages of their spread, online social networks spread through pre-existing social communities, inducing further distortions. [ObCitationOfNeglectedOughtToBeClassicPaper: Schoenebeck, "Potential Networks, Contagious Communities, and Understanding Social Network Structure", arxiv:1304.1845.] As I write, you can see this happening with BlueSky. But I think the argument above would apply even if we signed up everyone to one social media site.)

*: Define "impressions" as the product of "number of posts per unit time" and "number of followers". If those both have power-law tails, with exponents \( \alpha \) and \( \beta \) respectively, and are independent, then impressions will have a power-law tail with exponent \( \alpha \wedge \beta \), i.e., slowest decay rate wins. )To see this, set \( Z = XY \) so \( \log{Z} = \log{X} + \log{Y} \), and the pdf of \( \log{Z} \) is, by independence, the convolution of the pdfs of \( \log{X} \) and \( \log{Y} \). But those both have exponential tails, and the slower-decaying exponential gives the tail decay rate for the convolution.) The argument is very similar if both are log-normal, etc., etc. --- This does not account for amplification by repetition, algorithmic recommendations, etc. ^

**: Someone sufficiently flame-proof could make a genuinely valuable study of this point by scraping the public various fora for written erotica and doing automated content analysis. I'd bet good money that the right tail of prolificness is dominated by authors with very niche interests. [Or, at least, interests which were niche at the time they started writing.] But I could not, in good conscience, advise anyone reliant on grants to actually do this study, since it'd be too cancellable from too many directions at once. ^

***: As a small example I recently overheard in a grocery store, "her hair didn't used to be such a Republican blonde" is a perfectly comprehensible statement. ^

Actually, "Dr. Internet" Is the Name of the Monsters' Creator; Kith and Kin

Posted at April 21, 2025 21:17 | permanent link

April 16, 2025

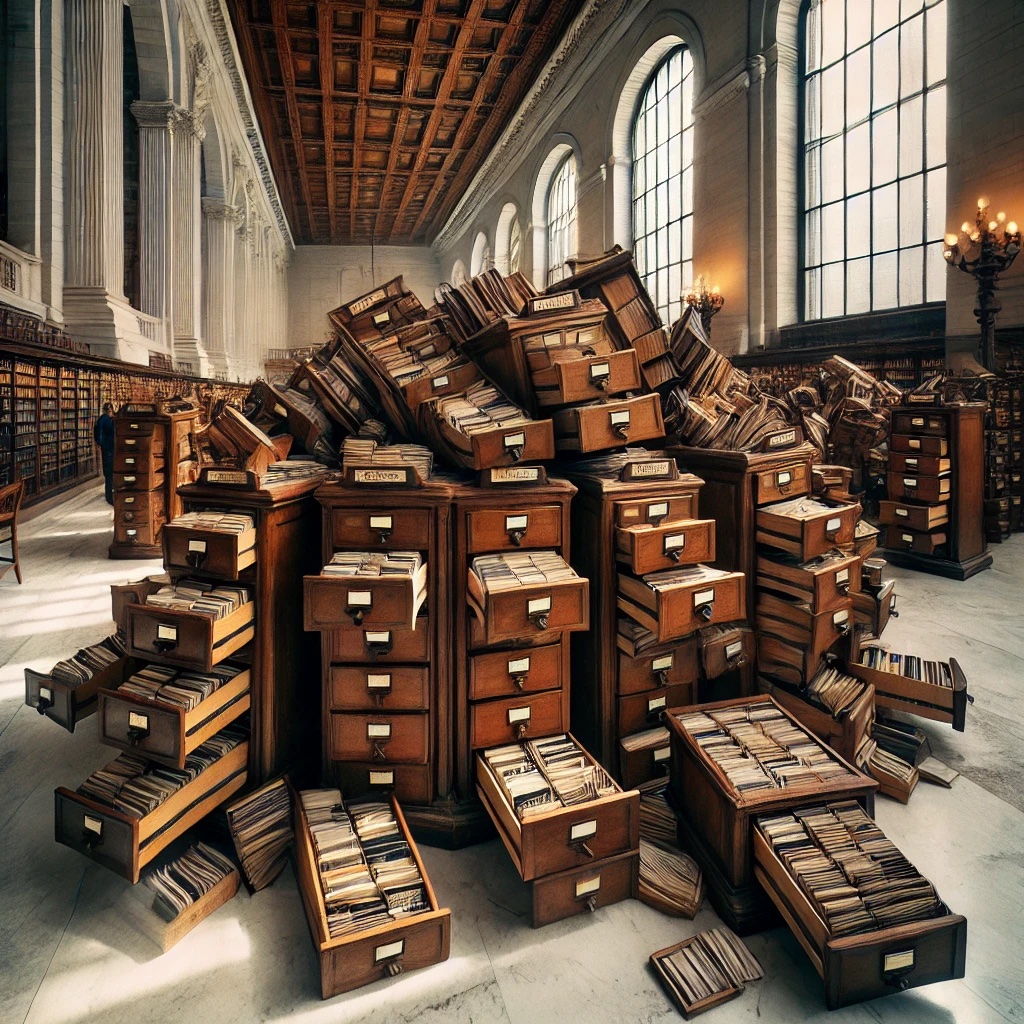

On Feral Library Card Catalogs, or, Aware of All Internet Traditions

Attention conservation notice: Almost 3900 words of self-promotion for an academic paper about large language models (of all ephemeral things). Contains self-indulgent bits trimmed from the published article, and half-baked thoughts too recent to make it in there.

For some years now, I have been saying to anyone who'll listen that the best way to think about large language models and their kin is due to the great Alison Gopnik, and it's to regard them as cultural technologies. All technologies, of course, are cultural in the sense that they are passed on from person to person, generation to generation. In the process of leaping from mind to mind, cultural content always passes through some external, non-mental form: spoken words, written diagrams, hand-crafted models, demonstrations, interpretive dances, or just examples of some practice carried out by the exemplifier's body [1]. A specifically cultural technology is one that modifies that very process of transmission, as with writing or printing or sound recording. That is what LLMs do; they are not so much minds as a new form of information retrieval.

I am very proud to have helped play a part in giving Gopnikism [2] proper academic expression:

- Henry Farrell, Alison Gopnik, CRS and James Evans, "Large AI models are cultural and social technologies", Science 387 (2025): 1153--1156 [should-be-public link]

- Abstract: Debates about artificial intelligence (AI) tend to revolve around whether large models are intelligent, autonomous agents. Some AI researchers and commentators speculate that we are on the cusp of creating agents with artificial general intelligence (AGI), a prospect anticipated with both elation and anxiety. There have also been extensive conversations about cultural and social consequences of large models, orbiting around two foci: immediate effects of these systems as they are currently used, and hypothetical futures when these systems turn into AGI agents --- perhaps even superintelligent AGI agents. But this discourse about large models as intelligent agents is fundamentally misconceived. Combining ideas from social and behavioral sciences with computer science can help us to understand AI systems more accurately. Large models should not be viewed primarily as intelligent agents but as a new kind of cultural and social technology, allowing humans to take advantage of information other humans have accumulated.

What follows is my attempt to gloss and amplify some parts of our paper. My co-authors are not to be blamed for what I say here: unlike me, they're constructive scholars.

Myth and Information Retrieval

To put things more bluntly than we did in the paper: the usual popular and even academic debate over these models is, frankly, conducted on the level of myths (and not even of mythology). We have centuries of myth-making about creating intelligences and their consequences [3], Tampering with Forces Man Was Not Meant to Know, etc. Those myths have hybridized with millennia of myth-making about millenarian hopes and apocalyptic fears. [4] This is all an active impediment to understanding.

LLMs are parametric probability models of symbol sequences, fit to large corpora of text by maximum likelihood. By design, their fitting process strives to reproduce the distribution of text in the training corpus [5]. (The log likelihood is a proper scoring function.) Multi-modal large models are LLMs yoked to models of (say) image distributions; they try to reproduce the joint distribution of texts and images. Prompting is conditioning: the output after a prompt is a sample from the conditional distribution of text coming after the prompt (or the conditional distribution of images that accompany those words, etc.). All these distributions are estimated with a lot of smoothing: parts of the model like "attention" (a.k.a. kernel smoothing) tell the probability model when to treat different-looking contexts as similar (and how closely similar), with similar conditional distributions. This smoothing, what Andy Gelman would call "partial pooling", is what lets the models respond with sensible-looking output, rather than NA, to prompts they've never seen in the training corpus. It also, implicitly, tells the model what to ignore, what distinctions make no difference. This is part (though only part) of why these models are lossy.

(The previous paragraph, like our paper, makes no mention of neural networks, of vector embeddings as representations of discrete symbols, of LLMs being high-order Markov chains, etc. Those are important facts about current models. [That Markov models, of all things, can do all this still blows my mind.] But I am not convinced that these are permanent features of the technology, as opposed to the first things tried that worked. I really think we should know more about is how well other techniques for learning distributions of symbols sequences would work if given equivalent resources. I really do want to see someone try Large Lempel-Ziv. I also have a variety of ideas for combining Infini-gram with old distribution-learning procedures which I think would at the very least make good student projects. [I'm being a bit cagey because I'd rather not be scooped; get in touch if you're interested in collaborating.] I am quite prepared for all of these Mad Schemes to work less well than conventional LLMs, but then I think the nature and extent of the failures would be instructive. In any case, the argument we're making about these artifacts does not depend on these details of their innards.)

What follows from all this?

- These are ways of interpolating, extrapolating, smoothing, and sampling from the distribution of public, digitized representations we [6] have filled the Internet with. Now, most people do not have much experience with samplers --- certainly not with devices that sample from complex distributions with lots of dependencies. (Games of chance are built to have simple, uniform distributions.) (In fact, maybe the most common experience of such sampling is in role-playing games.) But while this makes them a novel form of cultural technology, they are a cultural technology.

- They are also a novel form of social technology. They create a technically-mediated relationship between the user, and the authors of the documents in the training corpora. To repeat an example from the paper, when someone uses a bot to write a job-application letter, the system is mediating a relationship between the applicant and the authors of hundreds or thousands of previous such letters. More weakly, the system is also mediating a relationship between the applicant and the authors of other types of letters, authors of job-hunting handbooks, the reinforcement-learning-from-human-feedback workers [7], etc., etc. (If you ask it how to write a regular expression for a particular data-cleaning job, it is mediating between you and the people who used to post on Stack Overflow.) Through the magic of influence functions, those with the right accesses can actually trace and quantify this relationship.

- These aren't agents with beliefs, desires and intentions. (Prompting them to "be an agent" is just conditioning the stochastic process to produce the sort of text that would follow a description of an agent, which is not the same thing.) They don't even have goals in the way in which a thermostat, or lac operon repressor circuit, have goals. [8] They also aren't reasoning systems, or planning systems, or anything of that sort. Appearances to the contrary are all embers of autoregression. (Some of those embers are blown upon by wishful mnemonics.)

I was (I suspect) among the last cohorts of students who were routinely taught how to use paper library card catalogs. Those, too, were technologies for bringing inquirers into contact with the works of other minds. You can worry, if you like, that LLMs and their kin are going to grow into uncontrollable artificial general intelligences, but it makes about as much sense as if I'd had nightmares about card catalogs going feral.

Complex Information Processing, and the Primal Scene of AI

Back when all this was beginning, in the spring of 1956, Allen Newell and Herbert Simon thought that "complex information processing" was a much better name than "artificial intelligence" [9]:

The term "complex information processing" has been chosen to refer to those sorts of behaviors --- learning, problem solving, and pattern recognition --- which seem to be incapable of precise description in any simple terms, or perhaps, in any terms at all. [p. 1]

Even though our language must still remain vague, we can at least be a little more systematic about what constitutes a complex information process.[p. 6]

- A complex process consists of very large numbers of subprocesses, which are extremely diverse in their nature and operation. No one of them is central or, usually, even necessary.

- The elementary component processes need not be complex; they may be simple and easily understood. The complexity arises wholly from the pattern in which these processes operate.

- The component processes are applied in a highly conditional fashion. In fact, large numbers of the processes have the function of determining the conditions under which other processes will operate.

If "complex information processing" had become the fixed and common name, rather than "artificial intelligence", there would, I think, be many fewer myths to contend with. To use a technical but vital piece of meta-theoretical jargon, the former is "basically pleasant bureaucrat", the latter is "sexy murder poet" (at least in comparison).

Newell and Simon do not mention it, explicitly, in their 1956 paper, but the component processes in a complex information-processing system can be hard-wired machines, or flexible programmed machines, or human beings, or any combination of these. Remember that Simon was, after all, a trained political scientist whose first book was Administrative Behavior and who had, in fact, worked as a government bureaucrat, helping to implement the Marshall Plan. Even more, the first time Newell and Simon ran their Logic Theorist program (described in that paper), they ran it on people, because the electronic computer was back-ordered. I will let Simon tell the story:

Al [Newell] and I wrote out the rules for the components of the program (subroutines) in English on index cards, and also made up cards for the contents of the memories (the axioms of logic). At the GSIA [= Graduate School of Industrial Administration] building on a dark winter evening in January 1956, we assembled my wife and three children together with some graduate students. To each member of the group, we gave one of the cards, so that each person became, in effect, a component of the LT computer program --- a subroutine that performed some special function, or a component of its memory. It was the task of each participant to execute his or her subroutine, or to provide the contents of his or her memory, whenever called by the routine at the next level above that was then in control.So we were able to simulate the behavior of LT with a computer constructed of human components. Here was nature imitating art imitating nature. The actors were no more responsible for what they were doing than the slave boy in Plato's Meno, but they were successful in proving the theorems given them. Our children were then nine, eleven, and thirteen. The occasion remains vivid in their memories.

[Models of My Life, ch. 13, pp. 206--207 of the 1996 MIT Press edition.]

The primal scene of AI, if we must call it that, is thus one of looking back and forth between a social organization and an information-processing system until one can no longer tell which is which.

All-Access Pass to the House of Intellect

Lots of social technologies can be seen as means of effectively making people smarter. Participants in a functioning social institution will act better and more rationally because of those institutions. The information those participants get, the options they must choose among, the incentives they face, all of these are structured --- limited, sharpened and clarified --- by the institutions, which helps people think. Continued participation in the institution means facing similar situations over and over, which helps people learn. Markets are like this; bureaucracies are like this; democracy is like this; scientific disciplines are like this. [10] And cultural tradition are like this.

Let me quote from an old book that had a lot of influence on me:

Intellect is the capitalized and communal form of live intelligence; it is intelligence stored up and made into habits of discipline, signs and symbols of meaning, chains of reasoning and spurs to emotion --- a shorthand and a wireless by which the mind can skip connectives, recognize ability, and communicate truth. Intellect is at once a body of common knowledge and the channels through which the right particle of it can be brought to bear quickly, without the effort of redemonstration, on the matter in hand.

Intellect is community property and can be handed down. We all know what we mean by an intellectual tradition, localized here or there; but we do not speak of a "tradition of intelligence," for intelligence sprouts where it will.... And though Intellect neither implies nor precludes intelligence, two of its uses are --- to make up for the lack of intelligence and to amplify the force of it by giving it quick recognition and apt embodiment.

For intelligence wherever found is an individual and private possession; it dies with the owner unless he embodies it in more or less lasting form. Intellect is on the contrary a product of social effort and an acquirement.... Intellect is an institution; it stands up as it were by itself, apart from the possessors of intelligence, even though they alone could rebuild it if it should be destroyed....

The distinction becomes unmistakable if one thinks of the alphabet --- a product of successive acts of intelligence which, when completed, turned into one of the indispensable furnishings of the House of Intellect. To learn the alphabet calls for no great intelligence: millions learn it who could never have invented it; just as millions of intelligent people have lived and died without learning it --- for example, Charlemagne.

The alphabet is a fundamental form to bear in mind while discussing ... the Intellect, because intellectual work here defined presupposes the concentration and continuity, the self-awareness and articulate precision, which can only be achieved through some firm record of fluent thought; that is, Intellect presupposes Literacy.

But it soon needs more. Being by definition self-aware, Intellect creates linguistic and other conventions, it multiplies places and means of communication....

The need for rules is a point of difficulty for those who, wrongly equating Intellect with intelligence, balk at the mere mention of forms and constraints --- fetters, as they think, on the "free mind" for whose sake they are quick to feel indignant, while they associate everything dull and retrograde with the word "convention". Here again the alphabet is suggestive: it is a device of limitless and therefore "free" application. You can combine its elements in millions of ways to refer to an infinity of things in hundreds of tongues, including the mathematical. But its order and its shapes are rigid. You cannot look up the simplest word in any dictionary, you cannot work with books or in a laboratory, you cannot find your friend's telephone number, unless you know the letters in their arbitrary forms and conventional order.---Jacques Barzun, The House of Intellect (New York: Harper, 1959), pp. 3--6

A huge amount of cultural and especially intellectual tradition consists of formulas, templates, conventions, and indeed tropes and stereotypes. To some extent this is to reduce the cognitive burden on creators: this has been extensively studied for oral culture, such as oral epics. But formulas also reduce the cognitive burden on people receiving communications. Scientific papers, for instance, within any one field have an incredibly stereotyped organization, as well as using very formulaic language. One could imagine a world where every paper was supposed to be a daring exploration of form as well as content, but in reality readers want to be able to check what the reagents were, or figure out which optimization algorithm was used, and the formulaic structure makes that much easier. This is boiler-plate and ritual, yes, but it's not just boiler-plate and ritual, or at least not pointless ritual [11].

Or, rather, the formulas make things easier to create and to comprehend once you have learned the formulas. The ordinary way of doing so is to immerse yourself in artifacts of the tradition until the formulas begin to seep in, and to try your hand at making such artifacts yourself, ideally under the supervision of someone who already has grasped the tradition. (The point of those efforts was not really to have the artifacts, but to internalize the forms.) Many of the formulas are not articulated consciously, even by those who are deeply immersed in the tradition.

Large models have learned nearly all of the formulas, templates, tropes and stereotypes. (They're probability models of text sequences, after all.) To use Barzun's distinction, they will not put creative intelligence on tap, but rather stored and accumulated intellect. If they succeed in making people smarter, it will be by giving them access to the external forms of a myriad traditions.

None of this is to say that large models are an unambiguous good thing:

- Maybe giving people access to the exoteric forms of tradition, without internalizing the habits that went along with them, is going to be a disaster.

- These technologies are already giving us entirely new political-economic struggles, especially about rewarding (or not) the creation of original content.

- As statistical summaries of large corpora, the models are intrinsically going to have a hard time dealing with rare situations. (More exactly: If there's an option, in model training, to do a little bit better in a very common situation at the cost of doing a lot worse in a very rare situation, the training process is going to take it, because it improves average performance.) In other words: sucks to try to use them to communicate unusual ideas, especially ideas that are rare because they are genuinely new.

- Every social technology has its ways of going horribly wrong. Often those arise from the kinds of information they ignore, which are also what make them useful. We know something about how markets fail, and bureaucracies, and (oh boy) democracies. We have no idea, yet, about the social-technology failure-modes of large models.

These are just a few of the very real issues which surround these technologies. (There are plenty more.) Spinning myths about superintelligence will not help us deal with them; seeing them for what they are will.

[1]: I first learned to appreciate the importance, in cultural transmission, of the alternation between public, external representations and inner, mental content by reading Dan Sperber's Explaining Culture. ^

[2]: I think I coined the term "Gopnikism" in late 2022 or early 2023, but it's possible I got it from someone else. (The most plausible source however is Henry, and he's pretty sure he picked it up from me.) ^

[3]: People have been telling the joke about asking a supercomputer "Is there a god?" and it answering "There is now" since the 1950s. Considering what computers were like back then, I contend it's pretty obvious that some part of (some of) us wants to spin myths around these machines. ^

[4]: These myths have also hybridized with a bizarre conviction that "this function increases monotonically" implies "this function goes to infinity", or even "this function goes to infinity in finite time". When this kind of reasoning grips people who, in other contexts, display a perfectly sound grasp of pre-calculus math, something is up. Again: mythic thinking. ^

[5]: Something we didn't elaborate on in the paper, and I am not going to do justice to here, is that one could deliberately not match the distribution of the training corpus -- one can learn some different distribution. Of course to some extent this is what reinforcement learning from human feedback (and the like) aims at, but I think the possibilities here are huge. Nearly the only artistically interesting AI image generation I've seen is a hobbyist project with a custom model generating pictures of a fantasy world, facilitated by creating a large artificial vocabulary for both style and content, and (by this point) almost exclusively training on the output of previous iterations of the model. In many ways, the model itself, rather than its images, is the artwork. (I am being a bit vague because I am not sure how much attention the projector wants.) Without suggesting that everything needs to be, as it were, postcards from Tlön, the question of when and how to "tilt" the distribution of large training corpora to achieve specific effects seems at once technically interesting and potentially very useful. ^

[6]: For values of "we" which include "the sort of people who pirate huge numbers of novels" and "the sort of people who torrent those pirated novel collections on to corporate machines". ^

[7]: If the RLHF workers are, like increasing numbers of online crowd-sourced workers, themselves using bots, we get a chain of technical mediations, but just a chain and not a loop. ^

[8]: I imprinted strongly enough on cybernetics that part of me wants to argue that an LLM, as an ergodic Markov chain, does have a goal after all. This is to forget the prompt entirely and sample forever from its invariant distribution. On average, every token it produces returns it, bit by bit, towards that equilibrium. This is not what people have in mind. ^

[9]: Strictly speaking, they never mention the phrase "artificial intelligence", but they do discuss the work of John McCarthy et al., so I take the absence of that phrase to be meaningful. Cf. Simon's The Sciences of the Artificial, "The phrase 'artificial intelligence' ... was coined, I think, right on the Charles River, at MIT. Our own research group at Rand and Carnegie Mellon University have preferred phrases like 'complex information processing' and 'simulation of cognitive processes.' ... At any rate, 'artificial intelligence' seems to be here to stay, and it may prove easier to cleanse the phrase than to dispense with it. In time it will become sufficiently idiomatic that it will no longer be the target of cheap rhetoric." (I quote from p. 4 of the third edition [MIT Press, 1996], but the passage dates back to the first edition of 1969.) Simon's hope has, needless to say, not exactly been achieved. ^

[10]: Markets, bureaucracies, democracies and disciplines are also all ways of accomplishing feats beyond the reach of individual human minds. I am not sure that cultural traditions are, too; and if large models are, I have no idea what those feats might be. (Maybe we'll find out.) ^

[11]: Incorporated by reference: Arthur Stinchcombe's When Formality Works, which I will write about at length one of these decades. ^

Update, later the same day: Fixed a few annoying typos. Also, it is indeed coincidence that Brad DeLong posted ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, & Co.: They Are Not Brains, They Are Kernel-Smoother Functions the same day.

Self-Centered; Enigmas of Chance; The Collective Use and Evolution of Concepts; Minds, Brains, and Neurons

Posted at April 16, 2025 12:25 | permanent link

April 01, 2025

The Books I Am Not Going to Write

Attention conservation notice: Middle-aged dad contemplating "aut liberi, aut libri" on April 1st.... and why I am not going to write them.

- Re-Design for a Brain

- W. Ross Ashby's Design for a Brain: The Origins of Adaptive

Behavior is a deservedly-classic and influential book. It also contains

a lot of sloppy mathematics, in some cases in important places. (For instance,

there are several crucial points where he implicitly assumes that deterministic

dynamical systems cannot be reversible or volume-preserving.) This project

would simply be re-writing the book so as to give correct proofs, with

assumptions clearly spelled out, and seeing how strong those assumptions need

to be, and so how much more limited the final conclusions end up being.

- Why I am not going to write it: It would be of interest to about five other people.

- The Genealogy of Complexity

- Why I am not going to write it: It no longer seems as important to me as it did in 2003.

- The Formation of the Statistical Machine Learning Paradigm, 1985--2000

- Why I am not going to write it: It'd involve a lot of work

I don't know how to do --- content analysis of CS conference

proceedings and interviews with the crucial figures while they're

still around. I feel like I could

fake my way throughget up to speed on content analysis, but oral history?!? - Almost None of the Theory of Stochastic Processes

- Why I am not going to write it: I haven't taught the class since 2007.

- Statistical Analysis of Complex Systems

- Why I am not going to write it: I haven't taught the class since 2008.

- A Child's Garden of Statistical Learning Theory

- Why I am not going to write it: Reading Ben Recht has made me doubt whether the stuff I understand and teach is actually worth anything at all.

- The Statistics of Inequality and Discrimination

- I'll just quote the course description:

Many social questions about inequality, injustice and unfairness are, in part, questions about evidence, data, and statistics. This class lays out the statistical methods which let us answer questions like "Does this employer discriminate against members of that group?", "Is this standardized test biased against that group?", "Is this decision-making algorithm biased, and what does that even mean?" and "Did this policy which was supposed to reduce this inequality actually help?" We will also look at inequality within groups, and at different ideas about how to explain inequalities between and within groups.

The idea is to write a book which could be used for a course on inequality, especially in the American context where we're obsessed by between-group inequalities, for quantitatively-oriented students and teachers, without either pandering, or pretending that being STEM-os lets us clear everything up easily. (I have heard too many engineers and computer scientists badly re-inventing basic sociology and economics in this context...)- Why I am not going to write it: Nobody wants to hear that these are real social issues; that understanding these issues requires numeracy and not just moralizing; that social scientists have painfully acquired important knowledge about these issues (though not enough); that social phenomena are emergent so they do not just reflect the motives of the people involved (in particular: bad things don't happen just because the people you already loathe are so evil; bad things don't stop happening just because nobody wants them); or that no amount of knowledge about how society is and could be will tell us how it should be. So writing the book I want will basically get me grief from every direction, if anyone pays any attention at all.

- Huns and Bolsheviks

- To quote an old notebook: "the Leninists were like the Chinggisids and the Timurids, and similar Eurasian powers: explosive rise to dominance over a wide area of conquest, remarkable horrors, widespread emulation of them abroad, elaborate patronage of sciences and arts, profound cultural transformations and importations, collapse and fragmentation leaving many successor states struggling to sustain the same style. But Stalin wasn't Timur; he was worse. (Likewise, Gorbachev was better than Ulugh Beg.)"

- Why I am not going to write it: To do it even half-right, relying entirely on secondary sources, I'd have to learn at least four languages. Done well or ill, I'd worry about someone taking it seriously.

- The Heuristic Essentials of Asymptotic Statistics

- What my students get sick of hearing me refer to as "the usual

asymptotics". A first-and-last course in statistical theory, for people who

need some understanding of it, but are not going to pursue it professionally,

done with the same level of mathematical rigor (or, rather, floppiness) as a

good physics textbook. --- Ideally of course it would also be useful for those

who are going to pursue theoretical statistics professionally, perhaps

through a set of appendices, or after-notes to each chapter, highlighting the

lies-told-to-children in the main text. (How to give those parts the acronym

"HFN", I don't know.)

- Why I am not going to write it: We don't teach a course like that, and it'd need to be tried out on real students.

- Actually, "Dr. Internet" Is the Name of the Monsters' Creator

- Why I am not going to write it: Henry will finally have had enough of my nonsense as a supposed collaborator and write it on his own.

- Logic Is a Pretty Flower That Smells Bad

- Seven-ish pairs of chapters. The first chapter in each pair highlights a

compelling idea that is supported by a logically sound deduction from

plausible-sounding premises. The second half of the pair then lays out the

empirical evidence that the logic doesn't describe the actual world at all.

Thus the book would pair Malthus on population with the demographic revolution

and Boserup, Hardin's tragedy of the commons with Ostrom, the Schelling model

with the facts of American segregation, etc. (That last is somewhat unfair to

Schelling, who clearly said his model wasn't an explanation of how we

got into this mess, but not at all unfair to many subsequent economists. Also,

I think it'd be an important part of the exercise that at least one of the

"logics" be one I find compelling.) A final chapter would reflect on

the role of good arguments in keeping bad ideas alive, the importance of scope

conditions, Boudon's "hyperbolic" account of ideology, etc.

- Why I am not going to write it: I probably should write it.

- Beyond the Orbit of Saturn

- Historical cosmic horror mind candy: in 1018, Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni

receives reports that the wall which (as the Sultan understands things)

Alexander built high in the Hindu Kush to contain Gog and Magog is decaying.

Naturally, he summons his patronized and captive scholars to figure out what to

do about this. Naturally, the rivalry between al-Biruni and ibn Sina flares

up. But there is something up there, trying to get out, something

not even the best human minds of the age can really comprehend...

- Why I am not going to write it: I am very shameless about writing badly, but I find my attempts at fiction more painful than embarrassing.

Posted at April 01, 2025 00:30 | permanent link

March 31, 2025

Books to Read While the Algae Grow in Your Fur, March 2025

Attention conservation notice: I have no taste, and no qualification to opine on pure mathematics, sociology, or adaptations of Old English epic poetry. Also, most of my reading this month was done at odd hours and/or while chasing after a toddler, so I'm less reliable and more cranky than usual.

- Philippe Flajolet and Robert Sedgewick, Analytic Combinatorics [doi:10.1017/CBO9780511801655]

- I should begin by admitting that I have never learned much

combinatorics, and never really liked what I did learn. To say my

knowledge topped out at Stirling's approximation to $n!$ is only

a mild exaggeration. Nonetheless, after reading this book, I think I begin to

get it. I'll risk making a fool of myself by explaining.

- We start with some class $\mathcal{A}$ of discrete, combinatorial objects, like a type of tree or graph obeying some constraints and rules of construction. There's a notion of "size" for these objects (say, the number of nodes in the graph, or the number of leaves in the tree). We are interested in counting the number of objects of size $n$. This gives us a sequence $A_0, A_1, A_2, \ldots A_n, \ldots$.

- Now whenever we have a sequence of numbers $A_n$, we can encode it in a "generating function" \[ A(z) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}{A_n z^n} \] and recover the sequence by taking derivatives at the origin: \[ A_n = \frac{1}{n!} \left. \frac{d^n A}{dz^n} \right|_{z=0} \] (I'll claim the non-mathematician's privilege of not worrying about whether the series converges, the derivatives exist, etc.) When I first encountered this idea as a student, it seemed rather pointless to me --- we define the generating function in terms of the sequence, so why do we need to differentiate the GF to get the sequence?!? The trick, of course, is to find indirect ways of getting the generating function.

- Part A of the book is about what the authors call the "symbolic method" for building up the generating functions of combinatorial classes, by expressing them in terms of certain basic operations on simpler classes. The core operations, for structures with unlabeled parts, are disjoint union, Cartesian product, taking sequences, taking cycles, taking multisets, and taking power sets. Each of these corresponds to a definite transformation of the generating function: if $\mathcal{A}$s are ordered pairs of $\mathcal{B}$s and $\mathcal{C}$s (so the operation is Cartesian product), then $A(z) = B(z) C(z)$, while if $\mathcal{A}$s are sequences of $\mathcal{B}$s, then $A(z) = 1/(1-B(z))$, etc. (Chapter I.) For structures with labeled parts, slightly different, but parallel, rules apply. (Chapter II.) These rules can be related very elegantly to constructions with finite automata and regular languages, and to context-free languages. If one is interested not just in the number of objects of some size $n$, but the number of size $n$ with some other "parameter" taking a fixed value (e.g., the number of graphs on $n$ nodes with $k$ nodes of degree 1), multivariate generating functions allow us to count them, too (Chapter III). (Letting $k$ vary for fixed $n$ of course gives a probability distribution.) When the parameters of a complex combinatorial object are "inherited" from the parameters of the simpler objects out of which it is built, the rules for transforming generating functions also apply.

- In favorable cases, we get nice expressions (e.g., ratios of polynomials) for generating functions. In less favorable cases, we might end up with functions which are only implicitly determined, say as the solution to some equation. Either way, if we now want to decode the generating function $A(z)$ to get actual numbers $A_1, A_2, \ldots A_n, \ldots$, we have to somehow extract the coefficients of the power series. This is the subject of Part B, and where the "analytical" part of the title comes in. We turn to considering the function $A(z)$ as a function on the complex plane. Specifically, it's a function which is analytic in some part of the plane, with a limited number of singularities. Those singularities turn out to be crucial: "the location of a function's singularities dictates the exponential growth of its coefficients; the nature of a functions singularities determine the subexponential factor" (p. 227, omitting symbols). Accordingly, part II opens with a crash course in complex analysis for combinatorists, the upshot of which is to relate the coefficients in power series to certain integrals around the origin. One can then begin to approximate those integrals, especially for large $n$. Chapter V carries this out for rational and "meromorphic" functions, ch. VI for some less well-behaved ones, with applications in ch. VII. Chapter VIII covers a somewhat different way of approximating the relevant integrals, namely the saddle-point method, a.k.a. Laplace approximation applied to contour integrals in the complex plane.

- Part C, consisting of Chapter IX, goes back to multivariate generating functions. I said that counting the number of objects with size $n$ and parameter $k$ gives us, at each fixed $n$, a probability distribution over $k$. This chapter considers the convergence of these probability distributions as $n \rightarrow \infty$, perhaps after suitable massaging / normalization. (It accordingly includes another crash course, in convergence-in-distribution for combinatorists.) A key technique here is to write the multivariate generating function as a small perturbation of a univariate generating function, so that the asymptotics from Part B apply.

- There are about 100 pages of appendices, to fill gaps in the reader's mathematical background. As is usual with such things, it helps to have at least forgotten the material.

- This is obviously only for mathematically mature readers. I have spent a year making my way through it, as time allowed, with pencil and paper at hand. But I found it worthwhile, even enjoyable, to carve out that time. §

- (The thing which led me to this, initially, was trying to come up with an answer to "what on Earth is the cumulative generating function doing?" If we're dealing with labeled structures, then the appropriate generating function is what the authors call the "exponential generating function", $A(z) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}{A_n z^n / n!}$. If $A$'s are built as sets of $B$'s, then $A(z) = \exp(B(z))$. Turned around, then, $B(z) = \log{A(z)}$ when $A$'s are composed as sets of $B$'s. So if the moments of a random variable could be treated as counting objects of a certain size, so $A_n = \mathbb{E}\left[ X^n \right]$ is somehow the number of objects of size $n$, and we can interpret these objects as sets, the cumulant generating function would be counting the number of set-constituents of various sizes. I do not regard this as a very satisfying answer, so I am going to have to learn even more math.)

- We start with some class $\mathcal{A}$ of discrete, combinatorial objects, like a type of tree or graph obeying some constraints and rules of construction. There's a notion of "size" for these objects (say, the number of nodes in the graph, or the number of leaves in the tree). We are interested in counting the number of objects of size $n$. This gives us a sequence $A_0, A_1, A_2, \ldots A_n, \ldots$.

- Arthur L. Stinchcombe, Information and Organizations [Open access]

- A series of essays on organizations --- mostly for-profit corporations, but also universities --- as information-processing systems. The main thesis is that organizations "[grow] toward sources of news, news about the uncertainties that most affect their outcomes" (pp. 5--6), and then react to that news on an appropriate (generally, quick) time-scale. This is a functionalist idea, but Stinchcombe is careful to try to make it work, making arguments about how an organization's need to perform these functions comes to be felt by actual people in the organization, people who are in positions to do something about it. (Usually, his arguments on this score are persuasive.) This is by far the best thing I've seen in sociology about social structures as information-processing systems; I'm a bit disappointed in myself that I didn't read it a long time ago. §

- Zach Weinersmith and Boulet, Bea Wolf

- The first part of Beowulf, through the defeat of Grendel,

adapted into a comic-book about joyously ill-behaved kids in an American

suburb. Rather incredibly, it works. §

- Thanks to Jan Johnson for the book!

- (Subsequently, in weirdly too-modern renditions of Beowulf.)

- Thanks to Jan Johnson for the book!

Books to Read While the Algae Grow in Your Fur; Mathematics; Automata and Calculating Machines; Enigmas of Chance; Commit a Social Science; The Dismal Science; The Collective Use and Evolution of Concepts; The Commonwealth of Letters

Posted at March 31, 2025 23:59 | permanent link

January 31, 2025

Books to Read While the Algae Grow in Your Fur, January 2025

Attention conservation notice: I have no taste, and no qualification to opine on ancient history, the anthropology of the transition to literacy, or even on feminist science fiction. Also, most of my reading this month was done at odd hours and/or while chasing after a toddler, so I'm less reliable and more cranky than usual.

- The Radch, the society in which we spend almost all our time and whose viewpoint we adopt, is, by our lights, an awful, evil place.

- The Radch is completely free of sexism, patriarchy and misogyny.

Let us recapitulate the educational experience of the Homeric and post-Homeric Greek. He is required as a civilised being to become acquainted with the history, the social organisation, the technical competence and the moral imperatives of his group. This group will in post-Homeric times be his city, but his city in turn is able to function only as a fragment of the total Hellenic world. It shares a consciousness in which he is keenly aware that he, as a Hellene, partakes. This over-all body of experience (we shall avoid the word 'knowledge') is incorporated in a rhythmic narrative or set of narratives which he memorises and which is subject to recall in his memory. Such is poetic tradition, essentially something he accepts uncritically, or else it fails to survive in his living memory. Its acceptance and retention are made psychologically possible by a mechanism of self-surrender to the poetic performance, and of self-identification with the situations and the stories related in the performance. Only when the spell is fully effective can his mnemonic powers be fully mobilised. His receptivity to the tradition has thus, from the standpoint of inner psychology, a degree of automatism which however is counter-balanced by a direct and unfettered capacity for action, in accordance with the paradigms he has absorbed. 'His not to reason why.' [ch. 11, pp. 198--199; any remaining glitches are, for once, due to OCR errors in the ProQuest electronic version and not my typing]Elsewhere, Havelock repeatedly speaks of "hypnotism". This is all, supposedly, what Plato is reacting against.

- We have an extensive anthropological record of non-literate societies all over the world, many of them possessing elaborate traditions of poetic arts and political sophistication. In none of them do we find populations hypnotized by oral epics which are also tribal encyclopedias.

- Regarded as encyclopedias, the Homeric epics are worthless. You could not, in fact, learn how to load a ship from the first book of the Iliad, though this is one of Havelock's repeated examples (starting on pp. 81--82). You could not actually learn any art from the Iliad, not even combined-infantry-and-chariot * tactics. (You could learn many vivid ways to describe violent death.) Havelock even realizes/admits this (p. 83: "[T]he descriptions are always typical rather than detailed. It was no doubt part of Plato's objection that this was so: the poet was not an expert."), but it does not seem to lead him to reconsider. One wonders what Havelock would make of the "technical" passages in science fiction, or for that matter in airport thrillers.

Books to Read While the Algae Grow in Your Fur; Writing for Antiquity; Scientifiction and Fantastica; Afghanistan and Central Asia

Posted at January 31, 2025 23:59 | permanent link

November 25, 2024

Tenure-Track Opening in Computational Social Science at CMU (a.k.a. Call to Pittsburgh, 2024 edition)

Attention conservation notice: Advertising an academic position in fields you don't work in, in a place you don't want to live, paying much less than the required skills can get from private industry.

We have a tenure-track opening at the intersection of statistics and complex social systems, a.k.a. computational social science:

The Department of Statistics and Data Science at Carnegie Mellon University invites applications for a tenure track position in Computational Social Science at the rank of Assistant Professor starting in Fall 2025. This position will be affiliated with the Institute for Complex Social Dynamics.The Department seeks candidates in the areas of social science statistics and data science, as well as related interdisciplinary fields. Potential areas of interest include network science, social simulation, data science for social good, simulation-based inference, cultural evolution, using large text and image corpora as data, and data privacy. Candidates with other research interests related to the work of both the Department and the Institute are also highly encouraged to apply.

The Institute for Complex Social Dynamics brings together scholars at Carnegie Mellon University who develop and apply mathematical and computational models to study large-scale complex social phenomena. The core members of the Institute are based in the Departments of Statistics and Data Science, Social and Decision Sciences, and Philosophy. Interests of the Institute include studies of the emergence of social behavior, the spread of misinformation, social inequality, and societal resilience.

As tenure-track faculty, the successful candidate will be expected to develop an independent research agenda, leading to publications in leading journals in both statistics and in suitable social-scientific venues; to teach courses in the department at both the undergraduate and graduate level; to supervise Ph.D. dissertations; to obtain grants; and in general to build a national reputation for their scholarship. The candidate will join the ICSD as a Core Member, and help shape the future of the Institute.

CMU's statistics department is unusually welcoming to those without traditional disciplinary backgrounds in statistics (after all, I'm here!), and that goes double for this position. If this sounds interesting, then apply by December 15th. (I'm late in posting this.) If this sounds like it would be interesting to your doctoral students / post-docs / other proteges, then encourage them to apply.

(If you'd like to join the statistics department, but are not interested in

complex social dynamics what's wrong with you? we

have another tenure

track opening, where I'm not on the hiring committee.)

Posted at November 25, 2024 10:30 | permanent link

November 14, 2024

Come Post-Doc with Me!

Attention conservation notice: Soliciting applications for a limited-time research job in an arcane field you neither understand nor care about, which will at once require specialized skills and pay much less than those skills command in industry.

I am, for the first time, hiring a post-doc:

The Department of Statistics and Data Science at Carnegie Mellon University invites applicants for a two-year post-doctoral fellowship in simulation-based inference. The fellow will work with Prof. Cosma Shalizi of the department on developing theory, algorithms and applications of random feature methods in simulation-based inference, with a particular emphasis on social-scientific problems connected to the work of CMU's Institute for Complex Social Dynamics. Apart from by the supervisor, the fellow will also be mentored by other faculty in the department and the ICSD, depending on their interests and secondary projects, and will get individualized training in both technical and non-technical professional skills.Successful applicants will have completed a Ph.D. in Statistics, or a related quantitative discipline, by September 2025, and ideally have a strong background in non-convex and stochastic optimization and/or Monte Carlo methods, and good programming and communication skills. Prior familiarity with simulation-based inference, social network models and agent-based modeling will be helpful, but not necessary.

Basically, I need someone who is much better than I am at stochastic optimization to help out with the matching-random-features idea. But I hope my post-doc will come up with other things to do, unrelated to their ostensible project (God knows I did), and I promise not to put my name on anything unless I actually contribute. If you don't have a conventional background in statistics, well, I'm open to that, for obvious reasons.

Beyond that, the stats. department is a genuinely great and supportive place to work, I hope for fabulous things from ICSD, and CMU has a whole has both a remarkable number of people doing interesting work and remarkably low barriers between departments; Pittsburgh is a nice and still-affordable place to live. Apply, by 15 December!

--- If I have sold you on being a post-doc here, but not on my project or on me, may I interest you in working on social networks dynamics with my esteemed colleague Nynke Niezink?

(The post-doc ad is official, but this blog post is just me, etc., etc.)

Posted at November 14, 2024 23:20 | permanent link

October 17, 2024

30 Years of Notebooks

Attention conservation notice: Middle-aged dad has doubts about how he's spent his time.

In September 1994, I wanted to write a program which would filter the Usenet newsgroups I followed for the posts of most interest to me, which led me to writing out keywords describing what I was interested in. I don't remember why I started to elaborate the keywords into little essays and reading lists (perhaps self-clarification?), but I did, and then, because I'd just learned HTML and was playing around with hypertext, I put the document online. (My records say this was 3 October 1994, though that may have been fixing on a plausible date retroactively.) I've been updating those notebooks ever since, recording things-to-read as they crossed my path, recording my reading, and some thoughts. The biggest change in organization came pretty early: the few people who read it all urged me to split it from one giant file into many topical files, so I did, on 13 March 1995, ordered by last update, a format I've stuck to ever since (*).

This was not, of course, what I was supposed to be doing as a twenty-year-old physics graduate student. (Most of the notebook entries weren't even about physics.) Unlike a lot of ideas I had at that age, though, I stuck with it --- have stuck with it. Over the last thirty years, I've spent a substantial chunk of my waking hours recording references, consolidating what I understand by trying to explain it, and working out what I think by seeing what I write, by using Emacs to edit a directory of very basic HTML files. (I learned Emacs Lisp to write functions to do things like add links to arxiv.)

Was any of this a good use of my time? I couldn't begin to say. Long, long ago it became clear to me that I was never going to read more than a small fraction of the items I recorded as "To read:". I sometimes tell myself that it's a way of satiating my hoarding tendencies without actually filling my house with junk, but of course it's possible it's just feeding those tendencies. I do use the notebooks, though honestly the have-read portions are the most useful ones to me. Some of the notebooks have grown into papers, though many more which were intended to be seeds of papers have never sprouted. I know that some other people, from time to time, say they find them useful, which is nice. (Though I presume most people's reactions would range from bafflement to "wow, pretentious much?") Whether this justifies all those hours not writing papers / finishing any of my projected books / gardening / hanging out with friends / being with my family / playing with my cat (RIP) / drinking beer / riding my bike / writing letters / writing al-Biruni fanfic / actually reading, well...

The core of the matter, I suspect, is that if anyone does anything for a decade or three consistently, it becomes a very hard habit to break. By this point, the notebooks are so integrated into the way I work that it would take lots of my time and will-power to stop updating them, as long as I keep anything like my current job. So I will keep at it, and hope that it is, at worst, a cheap and harmless vice.

I never did write that Usenet filter.

*: A decade later, I started using blosxom, rather than completely hand-written HTML, and Danny Yee wrote me a cascading style sheet. I also was happy to use first HTMX, and then MathJax, to render math, rather than trying to put equations into HTML. ^.

Posted at October 17, 2024 09:30 | permanent link

October 04, 2024

The Professoriate Considered as a Super-Critical Branching Process

Attention conservation notice: Academic navel-gazing, in the form of basic arithmetic with unpleasant consequences that I leave partially implicit.

A professor at a top-tier research university who graduates only six doctoral students over a thirty year career is likely regarded by their colleagues as a bit of a slacker when it comes to advising work; it's easy to produce many more new Ph.D.s. (Here is a more representative case of some personal relevance.) That slacking professor has nonetheless reproduced their own doctorate six-fold, which works out to $\frac{\log{6}}{30} \approx$ 6% per year growth in the number of Ph.D. holders. Put this as a lower bound --- a very cautious lower bound --- on how quickly the number of doctorates could grow, if all those doctorate-holders became professors themselves. Unless faculty jobs also grow at 6% per year, which ultimately means student enrollment growing at 6% per year, something has to give. Student enrollment does not grow at 6% per year indefinitely (and it cannot, even if you think everyone should go to college); something gives. What gives is that most Ph.D.s will not be employed in the kind of faculty position where they train doctoral students. The jobs they find might be good, and even make essential use of skills which we only know how to transmit through that kind of acculturation and apprenticeship, but they simply cannot be jobs whose holders spawn more Ph.D.s.

The professoriate is a super-critical branching process, and we know how those end. (I am a neutron that didn't get absorbed by a moderator; that makes me luckier than those that did get absorbed, not better.) In the sustainable steady state, the average professor at a Ph.D.-granting institution should expect to have one student who also goes on to be such a professor in their entire career.

Anyone who takes this as a defense of under-funding public universities, of

adjunctification, or even of our society having more non-academic use for

quantitative skills than for humanistic learning, has trouble with reading

comprehension. Also, of course this is Malthusian reasoning; what

made Malthus wrong was not anticipating that what he called "vice"

could become universal the demographic transition. Let the reader

understand.

Posted at October 04, 2024 11:00 | permanent link

September 30, 2024

Books to Read While the Algae Grow in Your Fur, September 2024

Attention conservation notice: I have no taste, and no qualifications to opine on world history, or even on random matrix theory. Also, most of my reading this month was done at odd hours and/or while chasing after a toddler, so I'm less reliable and more cranky than usual.

- Marc Potters and Jean-Philippe Bouchaud, A First Course in Random Matrix Theory: for Physicists, Engineers and Data Scientists, doi:10.1017/9781108768900

- I learned of random matrix theory in graduate school; because of

my weird path, it was from

May's Stability and

Complexity in Model Ecosystems, which I read in 1995--1996. (I

never studied nuclear physics and so didn't encounter Wigner's ideas about

random Hamiltonians.) In the ensuing nearly-thirty-years, I've been more or

less aware that it exists as a subject, providing opaquely-named results about

the distributions of eigenvectors of matrices randomly sampled from various

distributions. It has, however, become clear to me that it's relevant to

multiple projects I want to pursue, and since I don't have one student working

on all of them, I decided to buckle down and learn some math. Fortunately,

nowadays this means downloading a pile of textbooks; this is the first of my

pile which I've finished.

- The thing I feel most confident in saying about the book, given my confessed newbie-ness, is that Potters and Bouchaud are not kidding about their subtitle. This is very, very much physicists' math, which is to say the kind of thing mathematicians call "heuristic" when they're feeling magnanimous *. I am still OK with this, despite years of using and teaching probability theory at a rather different level of rigor/finickiness, but I can imagine heads exploding if those with the wrong background tried to learn from this book. (To be clear, I think more larval statisticians should learn to do physicists' math, because it is really good heuristically.)

- To say just a little about the content, the main tool in here is the "Stieljtes transform", which for an $N\times N$ matrix $\mathbf{A}$ with eigenvalues $\lambda_1, \ldots \lambda_N$ is a complex-valued function of a complex argument $z$, \[ g^{\mathbf{A}}_N(z) = \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^{N}{\frac{1}{z-\lambda_i}} \] This can actually be seen as a moment-generating function, where the $k^{\mathrm{th}}$ "moment" is the normalized trace of $\mathbf{A^k}$, i.e., $N^{-1} \mathrm{tr}{\mathbf{A}^k}$. (Somewhat unusually for a moment generating function, the dummy variable is $1/z$, not $z$, and one takes the limit of $|z| \rightarrow \infty$ instead of $\rightarrow 0$.)

- The hopes are that (i) $g_N$ will converge to a limiting function as $N\rightarrow\infty$, \[ g(z) = \int{\frac{\rho(d\lambda)}{z-\lambda}} \] and (ii) the limiting distribution $\rho$ of eigenvalues can be extracted from $g(z)$. The second hope is actually less problematic mathematically **. Hope (i), the existence of a limiting function, is just assumed here. At a very high level, Potters and Bouchaud's mode of approach is to derive an expression for $g_N(z)$ in terms of $g_{N-1}(z)$, and then invoke the assumption (i), to get a single self-consistent equation for the limiting $g(z)$. There are typically multiple solutions to these equations, but also usually only one that makes sense, so the others are ignored ***.

- At this very high level, Potters and Bouchaud derive limiting distributions of eigenvalues, and in some cases eigenvectors, for a lot of distributions of matrices with random entries: symmetric matrices with IID Gaussian entries, Hermitian matrices with complex Gaussian entries, sample covariance matrices, etc. They also develop results for deterministic matrices perturbed by random noise, and a whole alternate set of derivations based on the replica trick from spin glass theory, which I do not feel up to explaining. These are then carefully applied to topics in estimating sample covariance matrices, especially in the high-dimensional limit where the number of variables grows with the number of observations. This in turn feeds in to a final chapter on designing optimal portfolios when covariances have to be estimated by mortals, rather than being revealed by the Oracle.

- My main dis-satisfaction with the book is that I left it without any real feeling for why the eigenvalue density of symmetric Gaussian matrices with standard deviation $\sigma$ approaches $\rho(x) = \frac{\sqrt{4\sigma^2 - x^2}}{2\pi \sigma^2}$, but other ensembles have different limiting distributions. (E.g., why is the limiting distribution only supported on $[-2\sigma, 2\sigma]$, rather than having, say, unbounded support with sub-exponential tails?) That is, for all the physicists' tricks used to get solution, I feel a certain lack of "physical insight" into the forms of the solutions. Whether any further study will make me happier on this score, I couldn't say. In the meanwhile, I'm glad I read this, and I feel more prepared to tackle the more mathematically rigorous books in my stack, and even to make some headway on my projects. §

- *: As an early example, a key step in deriving a key result (pp. 21--23) is to get the asymptotic expected value of such-and-such a random variable. Using a clever trick for computing the elements of an inverse matrix in terms of sub-matrices, they get a formula for the expected value of the reciprocal of that variable. They then say (eq. 2.33 on p. 22) that this is clearly the reciprocal of the desired limiting expected value, because after all fluctuations must be vanishing. ^

- **: We consider $z$ approaching the real axis from below, say $z=x-i\eta$ for small $\eta$. Some algebraic manipulation then makes the imaginary part of $g(x-i\eta)$ look like the convolution of the eigenvalue density $\rho$ with a Cauchy kernel of bandwidth $\eta$. A deconvolution argument then gives $\lim_{\eta \downarrow 0}{\mathrm{Im}(gx-i\eta)} = \pi \rho(x)$. This can be approximated with a finite value of $N$ and $\eta$ (p. 26 discusses the numerical error). ^

- ***: There is an interesting question about physicists' math here, actually. Sometimes we pick and choose among options that, as sheer mathematics, seem equally good, we "discard unphysical solutions". But sometimes we insist that counter-intuitive or even bizarre possibilities which are licensed by the math have to be taken seriously, physically (not quite "shut up and calculate" in its original intention, but close). I suspect that knowing when to do one rather than the other is part of the art of being a good theoretical physicist... ^

- The thing I feel most confident in saying about the book, given my confessed newbie-ness, is that Potters and Bouchaud are not kidding about their subtitle. This is very, very much physicists' math, which is to say the kind of thing mathematicians call "heuristic" when they're feeling magnanimous *. I am still OK with this, despite years of using and teaching probability theory at a rather different level of rigor/finickiness, but I can imagine heads exploding if those with the wrong background tried to learn from this book. (To be clear, I think more larval statisticians should learn to do physicists' math, because it is really good heuristically.)

- Fernand Braudel, The Perspective of the World, volume 3 of Civilization and Capitalism, 15th--18th Century

- This is the concluding volume of Braudel's trilogy, where he tries (as the

English title indicates) to give a picture of how the world-as-a-whole worked

during this period. It's definitely the volume I find least satisfying.