9 reviews

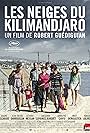

After a traumatic incident in their home, we see a trade unionist and his wife, hard-core socialists, questioning the turn their lives have taken over the years, too comfortable, too middle-class. Have we become like those rich people we used to fight? they wonder. Set in Marseilles, this story is compelling, cleverly structured, and very moving. Performances are outstanding, particularly from the two leads: Ariane Ascaride as Marie Claire and Jean Pierre Darrousin as Michel. They wonder about the choices they made, the confront their own children, and they make new choices trying to recover their lost passion for equality and class struggle. Photography is beautiful and includes several shots of the Marseille Harbour. I saw this film on Saturday 15 September 2012 at the Prince Charles in London as part of the London Labour Film Festival.

- marcoaponte

- Sep 15, 2012

- Permalink

What is solidarity? Solidarity in the union way? It seems easy in the beginning of this film, even if it's a decision which is to your own disadvantage. People have to go from the factory, there's a lottery and this union leader is among them. He didn't want any special treatment.

But this thinking and feeling is challenged, when one of his coworkers robs him and his wife. Why did he do that? It's a result of compromises from the union, leaving the robber and his kid brothers in misery.

So the screw is turned. Do you want revenge or do you blame yourself for lacking solidarity? The problem is solved in a way which shouldn't be mentioned here, but the answer is much easier than the questions.

But this thinking and feeling is challenged, when one of his coworkers robs him and his wife. Why did he do that? It's a result of compromises from the union, leaving the robber and his kid brothers in misery.

So the screw is turned. Do you want revenge or do you blame yourself for lacking solidarity? The problem is solved in a way which shouldn't be mentioned here, but the answer is much easier than the questions.

The question is simple but is far from being rhetorical: Should Art be an imitation of life, or should it be the other way around? The advocates of realism will surely make the first choice. In their view, life is full of ugliness that Art must faithfully portray, with absolutely no recourse to artificial embellishments. Often, the artist cannot even see the difference between realism and pessimism. In the case of cinema, in particular, the audience must leave the theater filled with dark thoughts and feelings of vanity. Happy ending is a taboo, and the positive message is hard to find (since life itself doesn't support it).

On the opposite side of realism, idealism reserves a more noble and ambitious role for Art; namely, to create high standards of thinking and behavior, thus offering psychological, ideological and aesthetic motivation for man to overcome the inherent weaknesses of his/her nature and reach these standards.

Robert Guédiguian's wonderful movie "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" (France, 2011) masterfully balances between these two opposite philosophical trends. On the one hand, there are the hard realities of our time: the economic recession and consequent unemployment, the growing youth resorting to crime, the refutation of the visions of the Left, and the (non-glorious) compromise of the latter with modern neoliberalism where there is no social care for the weak.

On the other hand –and these are the elements progressively dominating the film up to the final catharsis- scenes of incredible beauty parade through the eyes of the viewer, exhibiting a triumph of friendship, humanity, forgiveness, solidarity (a worthy substitute for absent state care)... And, above all, love and togetherness that keep a marriage alive over time and against the difficult challenges of life!

We left the theater full of positive thoughts and feelings. Finally leaving behind the painful memories of sickening movies by Michael Haneke or the Coen brothers...

On the opposite side of realism, idealism reserves a more noble and ambitious role for Art; namely, to create high standards of thinking and behavior, thus offering psychological, ideological and aesthetic motivation for man to overcome the inherent weaknesses of his/her nature and reach these standards.

Robert Guédiguian's wonderful movie "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" (France, 2011) masterfully balances between these two opposite philosophical trends. On the one hand, there are the hard realities of our time: the economic recession and consequent unemployment, the growing youth resorting to crime, the refutation of the visions of the Left, and the (non-glorious) compromise of the latter with modern neoliberalism where there is no social care for the weak.

On the other hand –and these are the elements progressively dominating the film up to the final catharsis- scenes of incredible beauty parade through the eyes of the viewer, exhibiting a triumph of friendship, humanity, forgiveness, solidarity (a worthy substitute for absent state care)... And, above all, love and togetherness that keep a marriage alive over time and against the difficult challenges of life!

We left the theater full of positive thoughts and feelings. Finally leaving behind the painful memories of sickening movies by Michael Haneke or the Coen brothers...

Although the philosophical issues behind the plot are interesting and the acting is good, the characters are one-dimensional. For instance, the husband is the sombre socialist enmeshed in class-guilt, his wife is the jovial, understanding and strong spouse, the criminal's brothers are picture perfect children and the criminal is pretty articulate for a low-life sociopath; the other characters are as predictable. None of the characters are real, in the sense that it is very unlikely that you will meet such stereotyped people in your life. It is all black and white, like in a children film.

- dbdumonteil

- Feb 22, 2014

- Permalink

- writers_reign

- Sep 13, 2012

- Permalink

- martinpersson97

- Apr 16, 2024

- Permalink