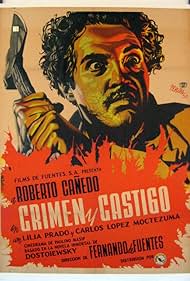

For this adaptation of Fyodor Dostoevsky's "Crime and Punishment," from late in the so-called Golden Age of Mexican cinema and from one of its more-acclaimed directors, I had to settle for an auto-translation to English from the original Spanish, but that was a relatively light burden to endure in this case. That's because I've been viewing a bunch of films, from around the world, based on the novel since reading it, which itself was a matter of Russian being interpreted into English, and many of the pictures pick and choose the same snippets from the book. It's unseemly how unoriginal they are at this. Moreover, this Mexican iteration is one of the more faithful in slavishly rendering those scenes of the story. Sure, there are a few differences: names have been changed (except "Sonya," the most universal of monikors from the book it seems), the crime doesn't involve the usual doubling of murders and is otherwise oddly prolonged--there's even a dissolve in the middle of it. The supposed Latin passion of the acting doesn't register much difference, either. At this point, I didn't need to understand one word throughout that any of the actors said, because I've already read and seen just about every aspect of the story that appears here. All the more reason that fidelity to story particulars is of little interest to me. That's not what is great about Dostoevsky's text, and no film will be through that path, either. What does make this one of some interest, however, is that it provides a look into an oft-neglected part of the cinematic world and transports the familiar story, as well as the spectator, to another place and time. Plus, it does do at least one smart thing with the plot.

The relatively few moments compared to the book that the Raskolinikov type, renamed "Ramón Bernal" here, walks the streets of, in this case, 1950s Mexico City are the most fascinating of the film--not only because they're a relief from the stagy flats, or vecindades, full of chatter that occupy most of the proceedings, but also because it offers the spectator a bit of virtual tourism. Of course, one can experience some of that studying the filmmaking practices of yesteryear, too, but I'm afraid this one, while proficient technically, it's also mostly prosaic. The continuity editing, slight dolly movements, sprinkling of close-ups, and shadowy lighting are all standard. The musical score is overblown in the typical classical cinema spirit--adding to the staginess in creating a conspicuously ersatz production. Some of the compositions look good, though, with objects or characters in the foreground framing those in the background to create depth of field. The best of these is the rather comical shot through an open door where Ramón is holding an axe while standing over the pawnbroker's corpse to form the backdrop of the shot as a man in the forefront obliviously walks past and up the stairs of the apartment building.

The smartest thing about the storytelling here is the employment of voiceover narration, which partially solves a problem in adaptation that has plagued many "Crime and Punishment" pictures. Dostoevsky wrote in the third-person omniscient perspective, or, otherwise put, from God's eye-view of the story--allowing the narrator to read characters' thoughts and float between subplots. Many, if not most, films, including this one, already employ omniscient narration, which only leaves the problem of how to render a character's stream of consciousness. Even most Dostoevsky adaptations tend to rely on the usual actorly conveyance, but some include voiceover narration. Those that do seem to come from the noir tradition, of which this may be the first one. Indeed, "Crime and Punishment" seems a natural fit for noir tendencies, shady environments, moral anxieties and fatalism. This one even begins with a glimpse of a flashforward to the scene of the crime underlying the opening credits, and the plot proper begins and ends with Raskolnikov rambling in his own head.